The amount of populist narrative and related hysteria have been visible in the political and quotidian life of the Czech republic for almost a decade. In the recent European Commission’s rule of law report, the Czech republic has been criticised for governmental conflict of interests, struggles to implement their anti-corruption strategy and the insufficient plurality and freedom of the media.

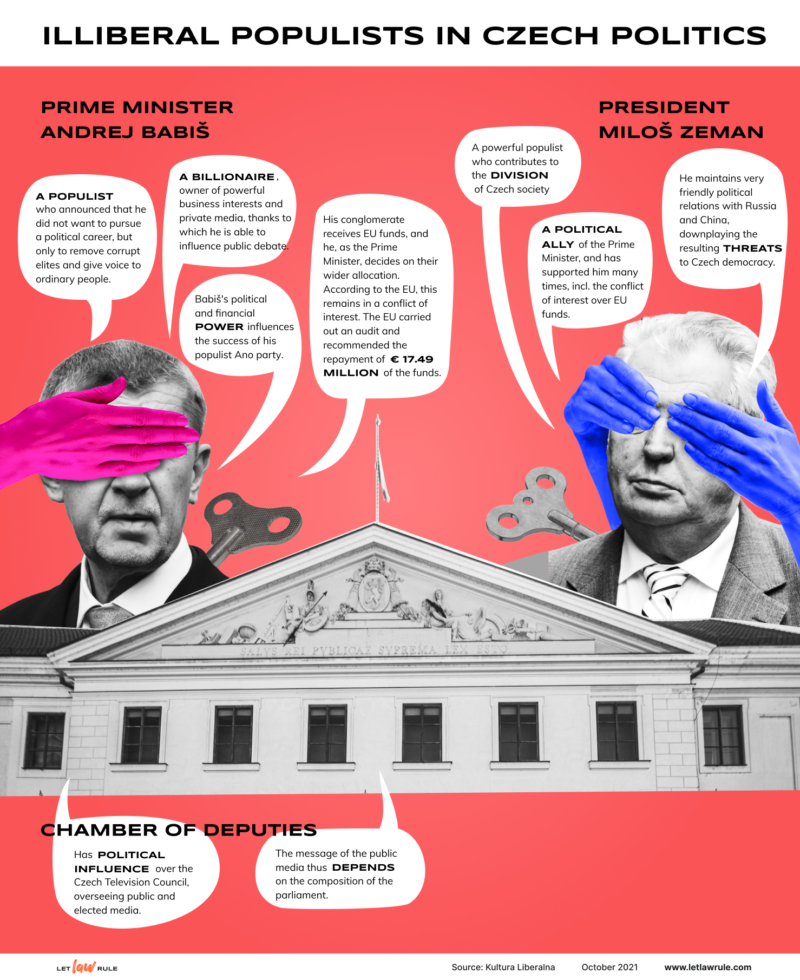

- One of the most important figures in the Czech crisis of the rule of law has been the Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, a billionaire populist who has used the state to strengthen the power of his own companies. Is also the owner of several private media through which he has been able to influence the political debate.

- Babis’ wealth and attitude are important to the rise and success of the Ano party, currently one on the the strongest populist party in Czech politics.

- Babiš has used both the migration crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic to his own populist agenda and his political interests.

- Babiš has a very strong political ally in the form of President Miloš Zeman. He is another powerful figure of Czech politics and a controversial populist, who has contributed to the further division of Czech society. The president maintains very friendly political relations with Russia and China, while at the same time downplaying the potential threats to Czech democracy that may result from some of these relations.

- Chamber of Deputies has political influence on the election of Czech Television Council and Czech Radio Council, overseeing public media. Thus, the attitude of the media councils to public media they oversee, in a certain way depends on the composition of the Chamber.

In the recent European Commission’s rule of law report, the Czech republic has been criticised for governmental conflict of interests, struggles to implement their anti-corruption strategy and the insufficient plurality and freedom of the media. Indeed, the level of corruption in the Czech republic is still perceived as relatively high. Until September 2021 isAndrej Babiš the billionaire, leader of the biggest parliamentary party ANO, and under investigation for conflicts of interest and EU fraud, was the prime minister. The president Miloš Zeman, a political figure from the 1990’s and the first president elected directly by citizens is serving his second term, and is often criticised for his controversial statements and friendly ties with Russia and China. The so-called migration crisis has fuelled populist political projects in the country, whilst publicly owned media are often targeted by certain populist politicians. In addition to these, the COVID-19 pandemic has shaken the country and its political stability, resulting in the appointment of five different ministers of health. Nevertheless, the strength of populist parties in Czechia seems to be holding strong.

Andrej Babiš and the rise of his populist party

Andrej Babiš entered Czech politics in 2011, famously proclaiming that he never actually wanted to be a politician. In 2012, he established a political movement, ANO 2011 (abbr. ANO), whose president he remains until today. From the beginning, the movement could be characterised as populist, criticising the establishment and corruption in Czech politics. Babiš, the second-richest person in the Czech Republic, owner of the Agrofert conglomerate, and Mafra media group, presented himself as an established businessman with no need to steal or be bribed, therefore entering the Czech politics solely to change it for the better. Shortly after its creation, ANO succeeded in the 2013 parliamentary elections, becoming the second biggest party in the lower chamber of the Parliament with 47 seats, behind the victorious ČSSD with 50 seats. These two biggest parties formed a coalition with KDU-ČSL (14 seats), gaining the necessary majority of 101 votes in the Chamber of deputies. In the 2014 European parliamentary elections, ANO secured 4 seats, the highest number of seats of all Czech political parties.

The important tool enabling the huge victory of ANO, a hitherto unknown and politically irrelevant movement was also its extensive, intensive and expensive marketing campaign. The final costs for the campaign were nearly 150 million czech crowns (about 6 million euros), making it the most expensive campaign of those elections (for reference the campaign of the winning ČSSD did cost nearly 90 million czech crowns, or 3.5 million euros). Given the budget, ANO was able to afford a team of marketing experts, allowing it to secure the position of the second biggest party in the Chamber of deputies. The party’s use of social media (Facebook, twitter) was relatively novel in Czech politics and ANO has mastered and continues to successfully use it today. One of the examples of the type of marketing ANO was able to afford was a TV commercial for a chicken producer, which was a company in the Agrofert concern, owned by Babiš. Screened on TV directly before the elections, the commercial starred the national hockey star and hero Jaromír Jágr alongside Andrej Babiš.

According to surveys, ANO has managed to address the electorate from all income levels, age groups and different levels of education, including people who have not previously voted and people who used to vote for other parties (ODS, TOP09 or ČSSD). In its campaign, ANO managed to accentuate the inability of the other “traditional” parties to act as they were suffering from their own internal problems and instability. Therefore, they have managed to address younger people who are not used to continuously voting for the traditional parties, as well as voters who were fed up with the constant drama of Czech politics and wanted to see someone with the “clean slate”.

In 2017 ANO won the next Czech parliamentary elections, gaining 78 seats out of 200 seats in the Chamber of deputies. The president Zeman entrusted Babiš with the appointment of the government and later appointed him the Prime Minister. If Miloš Zeman and Andrej Babiš were had agreed with each other up to that point, since the elections they have become allies and throughout Babiš’ governance, they have both used populism to promote their goals.

President Zeman – the disruptor of constitutional rules

The figure of the Czech president Zeman and his political role is rather controversial. Although being elected within a parliamentary democracy, where in compliance with the constitution, his role should be rather formal, he continuously manages to bend the constitutional traditions and create conflict in Czech politics. As was already mentioned, Zeman and Babiš have become close allies. After the elections in 2017, Zeman appointed Babiš with the prerogative of appointing the government, despite the fact that majority of the parliamentary parties refused to cooperate with him because of his conflicts of interest and criminal proceedings. This goes against the constitutional tradition, where the president usually appoints a person to the role of Prime Minister who is capable of gaining majority support in the Parliament. Zeman also supported Babiš during the criminal proceedings, claiming that he has to be seen as innocent until he is found guilty by the court.

President Zeman has also faced a judicial complaint himself, directly after his election in 2013, for using false, xenophobic or nationalistic arguments during his presidential campaign. Even though the court agreed that some of his campaign claims could be seen as pedagogical or false, the intensity was not such that it was ground to annul the elections. In 2017, Zeman faced a constitutional claim for refusing to appoint a number of candidates for professors, even though according to the constitutional traditions this was always just a formality. The constitutional court decided on Zeman’s behalf and the complaint was unsuccessful. In 2019, Zeman faced another constitutional claim for severe breach of the constitution, initiated by the Senate. The complaint targeted Zeman’s actions, such as his refusal to appoint and dismiss members of parliament, or his support of the minority government of Babiš, which did not have the necessary support in the Parliament. However, the complaint was unsuccessful, as it was not supported by the lower Chamber of the Parliament, including votes against by ANO, SPD, ČSSD and the Communist party.

Conflict of interests on national and EU levels

The phrase “conflict of interests” became a byword in Czech politics in the second half of the last decade, with Prime minister Babiš being under investigation by both Czech Police and the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) from 2015 to 2017.

In 2016, the Czech Parliament passed an amendment to the law on conflict of interests, informally known as “Lex Babiš”. The amendment prevented members of the Government from owning media, as well as from receiving funding from the state through their own companies. Based on the legal regulation, Babiš has moved his shares of Agrofert and SynBiol into two trusts, AB private trust I and AB private trust II. However, the uncertainties about the potential conflict of interests remained, as Babiš has remained the sole beneficent of those two trusts. The EU was not convinced that the conflict of interest between Babiš as a high political figure and him still benefiting from the conglomerate being subsidized by EU funding had been resolved. This led into an investigation by the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF), whose preliminary version of the EU audit reached 22 findings, with a recommendation to take action to repay EU funds totalling 17.49 million Euros. In 2019, the audit concluded that Babiš had a conflict of interest by taking part in decisions about the allocation of EU funds. The highest EU institutions are currently discussing conflict of interests and misuse of EU funds in the case of Czech PM Babiš.

Andrej Babiš could be perceived as preferring the economic interests of his own business conglomerate over the national interests, regarding his constant conflict of interests and his refusal to eliminate it. This tallies with his refusal to accept the findings of national bodies about the potential breach of national legislature, and a similar approach to the findings of EU bodies regarding the breach of EU rules. This attitude from the most powerful political figure in the country, alongside his enormous wealth, is all relevant for the rise and success of the currently strongest populist party in the Czech politics.

The rise of other populist movements

The general factors connected with the rise of the populist countries all over the world, such as the financial crisis, migration, globalisation and the strengthening of social media as a tool of political communication has all played a role in the Czech context as well. On the other hand, Czech republic is a state with low unemployment and the economy is strong compared to most other countries post-communist countries. The concrete consequences of the migration crisis have actually eluded the country: Due to the consistent refusal to participate in the EU’s relocation scheme during the migration crisis, the Czech republic remained untouched by the relocation. In 2020, the European Court of Justice ruled that the Czech Republic, along with Poland and Hungary, had violated their EU obligations by doing so. Despite the above socio-economic realities, frustration among the Czechs has only grown stronger, and in the last election in 2017, populist parties received a total of 40 % of all votes.

Indeed, the amount of populist narrative and related hysteria have been visible in the political and quotidian life of the Czech republic for almost a decade. In 2015, the Ministry of interior, which is responsible for the registration of political subjects, recorded a rise in populist subjects and initiatives, with themes focused on the refusal of immigration and Islam. One of the bigger ones was the initiative called “We don’t want Islam in Czechia” (Islám v ČR nechceme), which cooperated with the “Dawn” political party lead by Tomio Okamura (introduced in more detail below) and with the German movement PEGIDA. Aside from populist parties, however, the anti-migration measures were supported by other political players, such as the right-wing libertarian party Svobodní (Freedomites) and the traditional right-wing liberal ODS, as well as by the President, who is a strong supporter of anti-immigration measures. The narrative about the dangers of illegal immigration became so strong, that from July 2015, multiple demonstrations and protests against Islam and immigration were held throughout the country, most notably in Prague. These demonstrations were criticised for their xenophobia and racism, which was visible among the participants as well as the speakers who spoke at these events. At the summer demonstration against migration and the EU, some of the protestors carried around gallows. Among the speakers at one of the protests in November, on the national holiday celebrating the Velvet Revolution and the fall of the Communist regime, was the president Miloš Zeman. The right-wing anti-migration and anti-islam narrative caught people’s attention, and populism was on the rise.

We can understand populism as an ideology that perceives society as divided into two irreconcilable and homogenous enemy camps of ordinary people and corrupt elites. At the same time, populism believes that politics should be an expression of the people’s will. Populism also uses the narrative of a crisis, which can be of any kind, for example an economic crisis, migration crisis, or societal crisis. Usually, the elites are to be blamed for such crises, whilst populist parties appear as the only saviours, capable of bringing stability to the chaos. If we look at the main populist parties in the Czech political context, we can see that they use these above-mentioned tools very well.

One of the most popular populist movements in Parliament is “Úsvit” (The Dawn), formerly called The Dawn of Direct Democracy) led by Tomio Okamura, a Czech businessman of Japanese origin. The aim of the party is to strengthen direct democracy and represent Czech interests. The movement got into the Parliament in the early legislative elections in 2013, where they managed to get 14 seats, forming the 6th strongest party in the Chamber of Deputies. The political campaign of the Dawn for the following EP elections was focused on promoting a stricter migration policy, national values, and restricting the European Union’s powers, were all unsuccessful. In all of their political campaigns, Úsvit have used strong xenophobic rhetoric, openly criticised Islam and used it as a threat to scare the voters into voting for their party.

The narrative of protecting the national interests from the powerful Brussels is often used in the Czech populist context. Andrej Babiš used this momentum as well when he rejected the European Union’s refugee quotas, saying: “I will not accept refugee quotas [for the Czech Republic]”.

In 2015, after conflicts within the movement, the leader of Úsvit Okamura left and started another movement called Svoboda a Přímá Demokracie, SPD (“Freedom and Direct Democracy”). His departure was mostly due to the fact that he was unwilling to accept any new members into the movement, in order to be able to maintain absolute control and power. As the name of the newly created movement suggests, the aim was similar – nationalist, refusal of illegal immigration and Islam and a call for direct democracy in the form of appeal of politicians, judges and referendums as the main tool for deciding questions of the highest national importance.

Attacks on public media

The media in general, and public media in particular, should serve as an independent safeguard of democracy and a channel of unbiased and verified information. However, the state of the Czech public media has been rather unstable. For a while, The Czech Television Council, which is the body elected by the Parliament overseeing public broadcasting, has been under the direct control of the Chamber of Deputies. The almost 30 year old legal regulations allows for the lower chamber of the Parliament to appeal, as well as to revoke, the members of the TV Council. Although they should be independent, the members of the TV council are often elected as unofficial supporters of one of the political parties, mostly those with a political majority, as the members of the TV Council must be elected by the Chamber of deputies. This position gives the Chamber power to exercise political influence, and use backstage negotiations to receive support for particular candidates, who might indirectly support the party’s opinions on the TV Council. In recent years, there have been multiple candidates who were perceived as radical or controversial instead of independent, and who, instead of being experts or professional in the field were closer to the figures in the various populist movements. They have often criticised the functioning of the public TV and radio and expressed sceptical opinions about its overall existence. The role of the Czech president in the crisis of public media is not insignificant, as he has, on multiple occasions, criticised Czech TV and the work of its journalists, calling it a “part of the opposition” (this statement was later picked up by Russian propaganda) or refusing to communicate with particular Czech TV news shows. On the other hand, President Zeman has found favour in the private TV of the Czech businessman and political activist Soukup, who is known for his close contact with populist parties.

The role of the Chamber of Deputies to revoke the candidates also gives it the power to further influence the work of the TV Council and to threaten its independence. For example, for several years, the Chamber of Deputies refused to approve the annual reports of the Czech TV as it gave them grounds to revoke the TV Council. The president also played his role in this, as he has encouraged the Chamber of Deputies to not approve the annual reports of the Czech TV. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the instability around the public media continued, including an illegal revocation of the supervisory body of the Czech TV Council by the TV Council. An improvement in the situation can be expected either through political change, through personal change of the members of the TV Council, or by a new legal regulation providing for greater transparency in the election of the members of the TV Council, as well as greater independence of the exercise of their functions.

The COVID-19 crisis and challenges to the rule of law

The role of the Czech government during the COVID-19 pandemics was problematic on several levels. At the beginning of the pandemic, in spring 2020, the government proclaimed a state of national emergency that allowed it to adopt numerous emergency measures, including those restricting personal freedoms and rights. The measures then adopted included closing the national borders, closing shops and small businesses and closing schools. Once the situation improved, after the successful easing of restrictions during summer 2020, Prime Minister Babiš could be heard proclaiming that Czechia has the best in Covid situation. However, the Czech republic had multiple problems with the pandemic, including the fact that the government refused and was incapable of adopting any long term legislative measures that would allow it to deal with such crises in the long term on a predictable basis and most importantly in compliance with the Czech legal order. Instead, it has gone through multiple personnel crises, resulting in the appointment of five different Ministers of Health. The government and ministries adopted restriction measures, where the required measure needed to have a form of legal measure adopted by the Parliament. These did not have a legal basis in the Czech legal system, and were subsequently repealed by the courts for their illegality. Certain strict measures were temporarily postponed or lifted by the Government, seemingly based on populist calculations. For example, the Minister of Health intended to tighten up the restriction on the mandatory wearing of face masks, which was criticised by Babiš and subsequently and almost immediately revoked by the ministry, only to be reintroduced with other stricter measures after the regional elections in October 2020. Therefore, Babiš intentionally waited to introduce unpopular health measures until after the elections, despite the experts advising him to do so earlier. Throughout September 2020, despite the high number of COVID-19 infected people, the government refused to toughen the restrictions. However, after the election in October, a state of emergency was again announced, and the previously unnecessary heavier restrictions were imposed. However, the restrictions were lifted slightly before Christmas, not because of more favourable health conditions, but again as a presumably populist gesture. These populist tendencies and lack of objective information from the public bodies resulted in a lot of confusion and legal uncertainty within the society, giving ammunition to protesters and COVID-19 deniers.

We have seen anti-vaccination protests and meetings of people protesting against masks public spaces, as well as similar behaviour among politicians in Parliament. One of the members of the Chamber of Deputies, L. Volný, refused to wear a facemask during the Chamber meetings, for which he was banished on multiple occasions. Not coincidentally, Volný used to be a member of SPD and established another populist movement called “Volný blok” (Free bloc), focused on the already familiar agenda of protesting against vaccinations, COVID testing, migration and the EU.

The 2021 Parliamentary elections

The last elections into the Chamber of Deputies in October 2021 have showed how the COVID-19 pandemic and the performance of Babiš’ government have shaped the electorate, the main governmental parties such as ANO, and the opposition. Though ANO lost voters because of their role in the handling of the pandemic, it seems their role remains strong. They lost the elections, but still they are very strong in Parliament. As for the other parties, the opposition is getting stronger.

As a strong opposition to ANO, it seems the Pirate party, along with the Deputies (Piráti+Starostové) and the conservative SPOLU block have all emerged, who all have as one of their main aims the establish new parliamentary majority.

As we have seen, the composition of the Parliament has a distinct influence on the populist narrative and populist tendencies in the country and therefore the new composition of the Chamber of Deputies after the October election is crucial in establishing its direction and attitudes towards the populist agenda in the upcoming four years.

* Photo: Andrej Babiš on the ALDE Pre-Summit 22.03.2018, author: ALDE Party. Source: Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND © ALDE Party.