The Hungarian political system presents itself as a democracy, and the winner takes all. It ostensibly still a constitutional democracy, but has actually become a modern autocracy.

- The Hungarian constitution of 1989 was easy to amend. Each of its provisions could be changed by a two-thirds majority of the members of the unicameral legislative body. In turn, the winning party could win two-thirds of the seats in Parliament with just over 50 % of the vote thanks to the electoral system.

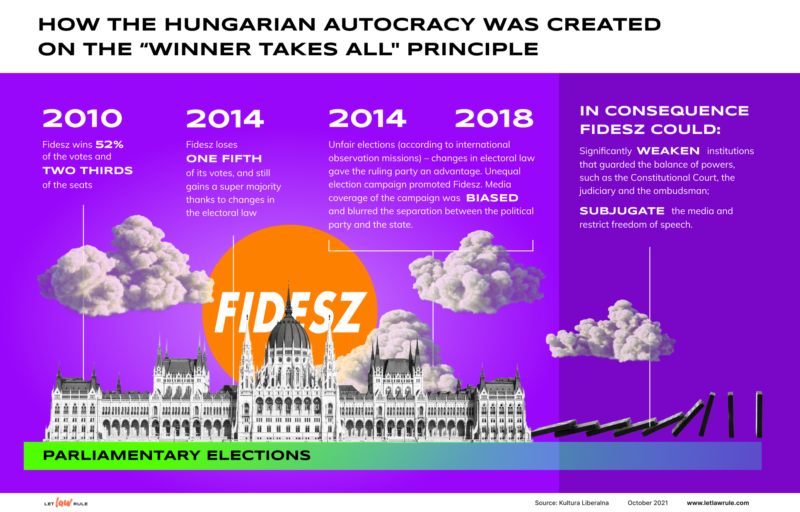

- In 2010, Fidesz won an overwhelming majority (68 %) of the parliamentary seats, with 53 % of the votes, allowing it to amend the Constitution or rewrite it completely. Parliament suspended key constitutional checks and facilitated a constitutional process that could take place without the participation of the opposition.

- The majority electoral mandate is implicit but not necessarily real. Many democratic majority elections are won by the largest and most important minority, not the majority. Winner-takes-all systems are renowned for delivering disproportionate results, with the largest minority bloc winning the majority of seats.

- The Hungarian constitutional system presents itself as a majority democracy. However, in this system, the legal mechanisms create an autocratic system, the key attribute of which is the pretence of a majoritarian democracy.

Though the Hungarian political system presents itself as a winner-takes-all democracy, observers encounter difficulties when attempting to label the system. Whilst ostensibly it still belongs to constitutional democracies, one might say that it is, in fact, majoritarian rather than consensual; populist instead of elitist; illiberal instead of liberal. Nevertheless, an analysis of the main procedures may help us better understand whether, in this system, legal mechanisms serve to govern the formation of a democratic majority rule or instead help to create an autocratic system.

Democracy as a procedure

Democracy and autocracy are mutually exclusive options. They are concepts of constitutional systems that are opposed in status and direction. In the early twentieth century, Hans Kelsen explained that in whatever institutional form, democracy has emerged as the only acceptable ground for constitutional architecture. Kelsen realised that democracy and autocracy are two opposing ideal types, out of which democracy is the more positive. After World War II, the binary logic of democracy versus autocracy became predominant. In Juan Jose Linz’s analysis, autocratic countries are often called non-democracies, encompassing totalitarian and authoritarian configurations.

Theorists of democracy offer plenty of positive understandings of democracy by justifying it in terms of procedural reasons. Major works single out the procedural side of the system as the defining characteristic of democracy. Democracy concerns collective decision-making procedures and decisions are made for, and binding on, the people. The procedural approach reflects on whether the government can be removed from office in peaceful and civilised procedures, that is, via well-defined, multiparty elections according to legally endorsed procedures and norms.

Democracy as a procedural matter also means majority rule. Under democracy, Kelsen discusses procedural mechanisms such as elections, parliamentary representation, and the relationship between majority and minority. Kelsen emphasises that the democracy of the modern state is “parliamentary democracy, in which the governing will of the community is shaped only by the majority of those elected by the majority of those possessing political rights.” In that sense, the self-rule of the people corresponds with the will of the majority of citizens.

Nevertheless, certain constitutional preconditions must be fulfilled even if one subscribes to a majoritarian conception of democracy. The majoritarian conception of democracy has implications requiring some procedural adjustments and limiting the outcomes of the majoritarian procedures. Perhaps everyone agrees that pluralist popular elections are a prerequisite for majoritarianism. In a democracy, multiple parties run for elections, and the government can be removed through a peaceful and civilised procedure. It is self-evident that in a democracy, a legal parliamentary opposition exists, and no repressive measures are imposed on them. The hallmark of democracy is that the opposition has a fair chance of returning to government; they are guaranteed appropriate speaking time in parliament and the same amount of airtime from public broadcasters. Both procedural theoretical approaches and democracy indexes emphasise that a system without regular elections in which all the people can participate cannot count as democracy. As such, universal and equal suffrage is the key here, along with the requirement of free and fair elections. Therefore, majority rule unconditionally includes certain procedural principles and rights, securing the democratic character of the voting procedures.

From a single-party system to democratic pluralism

After the Second World War, Stalinist autocracy prevailed in Hungary. In 1949 the communist-dominated Hungarian Parliament adopted a constitution – the first charter constitution to enter into force in the country – closely following the Soviet Stalinist Constitution of 1936. The regime based on legal and extra-legal repression occurred mainly in its first years and after the failure of the 1956 Revolution. Although the political system became gradually more consolidated, the rule of law and constitutionalism were alien to the soft autocracy, and the numerous constitutional changes that occurred during the communist period made little difference in this regard.

Like other communist constitutions, the provisions of the 1949 Constitution served purely ideological purposes; in other words, it was a political declaration and was never intended to serve as normative guidance in the actual use of political power, which was determined by the interests and whims of the Communist Party leadership. Formally, Hungary was considered to be a parliamentary system; in reality, however, the Communist Party made all crucial decisions, and most of these decisions were transposed into law through constitutional organs (Parliament, Presidium, or Council of Ministers).

The historical turning point for the transformation from the authoritarian regime to democracy was the autumn of 1989. The single-party system collapsed through a series of negotiations and compromises between the old regime and the democratic opposition. In formal terms, the 1989 Constitution was a mere modification of the 1949 Constitution. In substantive terms, however, the 1989 political transition breathed new life into the Hungarian Constitution. The 1989-born democracy can be characterised by the establishment of the main procedures and institutions of constitutionalism: free and fair multiparty elections, representative government, a parliamentary system, fundamental rights.

Compared to those of other European states, the 1989 Hungarian Constitution was easy to amend. Despite the fact that the Constitution could not be modified or amended by the ordinary law-making procedure according to a simple majority rule, it was regarded as relatively flexible rather than rigid, in the sense that it did not render any provision or principle unamendable, and it required only the votes of two-thirds of members of the one-chamber legislative body. Neither a referendum nor any other form of ratification (e.g., approval by the subsequent Parliament) was required for the adoption of a new constitution or a constitutional amendment. As a further factor, a party could secure two-thirds of the parliamentary seats with a little more than 50 per cent of the votes because Hungary had a mixed – majoritarian and proportionate – electoral system with single-member districts, county lists and a compensatory list. This kind of disproportionality enhanced the flexibility of the Constitution.

Moreover, there were serious social and political tensions at work under the surface of the democratic legal system. The political left and right were involved in a cold civil war and could not cooperate in partnership under, and for, a shared constitution. They not only saw each other as competitors in an election contest but also as enemies who were detrimental to national existence and progress. A poor tradition of democratic political procedures, weakness of civil society, imperfections of public education, and other sociological factors all made the constitutional balance fragile.

The winner takes all

The two-thirds rule and the disproportionate electoral structure began working in 2010. In the parliamentary elections, the then-opposition party Fidesz won a landslide majority of 68 per cent of the seats with 53 per cent of the votes. It was a majority sufficiently large enough to either amend the Constitution or rewrite it totally. The Parliament suspended key constitutional checks on legislation and facilitated a constitution-drafting process that could proceed without opposition involvement.

To lend the constitution-writing process legitimacy, a National Consultation Body was set up with the aim of sending a questionnaire to every citizen of Hungary. This questionnaire was composed of twelve issues, including the relationship between fundamental rights and obligations; the restriction of the public debt; the role of the family, public order, labour and health; the need for extra votes for mothers as a proxy for their children; the ban on levying taxes on the expenses related to child rearing; the protection of future generations; the conditions of public procurement; the unity of Hungarians across frontiers; the protection of natural diversity and national treasures; the protection of land and water; the need to include the sentencing to life imprisonment into the Constitution; and the obligation for a person to testify before a Parliamentary Commission if summoned. According to unaudited data, approximately 900,000 citizens filled in and sent back questionnaires (about 10 million inhabitants live in Hungary). The answers were in the midst of being processed when the draft new Constitution was submitted to Parliament. The draft text of the new Fundamental Law was released in March 2011. The parliamentary agenda ensured five days for the plenary debate about the concept, and four days about the details, meaning nine days from start to finish.

What makes the Hungarian constitutional transformation crucial from the perspective of this article is the new system’s appeal to majoritarianism. The elected leader of the country insists that the people get what the majority wants. On the face of it, repeated victories in multiparty elections are the most reliable indicators of majoritarian democracy at work. To illustrate this, Armin von Bogdandy holds that Hungary and Poland are illiberal democracies because these countries, while rejecting liberal values, have democratically elected governments. He argues that the clear democratic mandate includes that a governing majority is empowered to modify fundamental political and constitutional structures. Bogdandy highlights the powerful argument, much deployed by the governments of those countries that majoritarianism is the principle that gives form to democracy and national identity. “If a democratically elected governing majority modifies these fundamental political and constitutional structures — this most ‘sacred’ area of national sovereignty — there is strong reason to assume that neither the [European] Union nor other Member States should intervene.”

First, a vital reservation is needed here. The majoritarian electoral mandate is supposed but not necessarily real. Considerable empirical evidence shows that in many majoritarian democratic elections, the largest and most significant minority wins and not the majority. Winner-takes-all systems are famous for producing disproportionate results where the largest minority bloc of voters secures the majority of the seats. In Hungary, Orbán’s party could repeatedly win the parliamentary supermajority by a relative majority of votes. The party achieved by far the best result in 2010, with 2.7 million votes, while the number of eligible voters was more than 8 million, and the turnout was 5.1 million (64 %) in the first round and 3.6 million (46 %) in the second. In these and many other cases, the majority is real in the sense that the elections have been decided by a relative majority —that is, the largest minority— voting while the interests of the minorities are subordinated to that powerful group. The relative majority of the people is, in fact, bound together by political and cultural interests.

Second, in our view, the Hungarian constitutional system is not a majoritarian democracy; rather, it forms a modern autocracy. We argue elsewhere that the key attribute of the new autocratic system is the pretence of democracy. Given that democracy counts as the sole legitimate constitutional system today, the most salient new feature is that autocracy must pretend to be a democracy. Pretence means that legal change from a democracy into an autocracy is peaceful and coordinated. Unlike traditional autocrats who murdered or violently suppressed opponents, suspended legislation, and abolished courts, contemporary autocrats gain power peacefully and legitimise themselves through multi-party elections. Moreover, the new autocratic system behaves as if it were a constitutional democracy. Although contemporary autocrats have not given up the complete procedural mechanism of their ancestors, autocracy has undergone a modification; it now claims to abide by democratic principles but has fallen short of the legal preconditions for democracy.

Like many other modern autocratic systems, Hungary does not reject multiparty elections; on the contrary, the regime legitimises itself as a “democracy” through elections. Such autocracies retain multiparty elections and provide scope for the activities of opposition movements. What makes them distinctive is that the election is managed so as to deny opposition candidates a fair chance. Legal norms and practices ensure the dominance of the ruling party. For this reason, empirical proof of systematically unfair elections, biased electoral institutions, or other deficiencies of prerequisites for majoritarianism may contribute to the demonstration of an undemocratic system.

In Hungary, international observer missions concluded that the 2014 and 2018 parliamentary elections were unfair: the governing party enjoyed an undue advantage because of partisan changes in election law, unequal suffrage, gerrymandering, restrictive campaign regulations, far from an independent assessment of the election and biased media coverage that blurred the separation between political party and the state. While in 2010, Fidesz had won a 2/3 majority of the mandates with a 52 % victory; 2014 and 2018 had required even less than half the votes. No matter that between 2010 and 2014, they had lost a fifth of their supporters, they still won a supermajority due to the partisan changes in the legal system. In this way, Orbán could keep the process and outcome of the vote under control. As a result, the voting practice became hegemonic in its nature.

Likewise, the National Election Committee and the court of jurisdiction hinder all efforts to put questions of public interest to a referendum. In reality, only the prime minister has the privilege to initiate a national referendum, while the proposals of others (opposition parties, civil organisations, individuals) are systematically denied. The government-run “national consultation” process serves as a substitute for the referendum. These consultations come in the form of questionnaires, which the government sends directly to the electorate with questions. Neither the Fundamental Law nor any other law regulates national consultations. There is no independent verification of either the number of surveys returned or the answers. Since 2010, the government has launched several national consultations to ask the population, among other things, about the Fundamental Law (2011), “illegal migration” and terrorism (2015), the “Soros Plan”, and “Stopping Brussels” (2017) and lifting Covid restrictions (2021).

The Hungarian constitutional system presents itself as a winner-takes-all majoritarian democracy. Nevertheless, the examination of the procedural preconditions of democracy — electoral system, election bodies, procedural rights, and the rule of law — demonstrate that in this system, legal mechanisms do not serve to govern the formation of a legitimate majority rule. They instead create an autocratic system, whose key attribute is the pretence of majoritarian democracy.

Democratic reconstruction

Hungary needs a regime change, a transition again from autocracy to constitutional democracy. Without predicting the preconditions, procedures, or outcomes of a new democratic reconstruction in Hungary and elsewhere, we would like to bring the old concept of the “Glorious Revolution” into a new light.

Our contemporary concept of revolution goes back to Condorcet, who famously argued that revolution—radical, quick, progressive, often violent regime change—aims at freedom. Revolution is, of course, an empirical phenomenon. Revolutionaries believe that in the age of revolution, when despotism is unbearable, the spirit of liberty burns in the hearts of men and women.

Kriszta Kovács and Gábor Attila Tóth

* Photo: Budapest: Hungarian Parliament, author: Jorge Franganillo. Source: Flickr (CC BY 2.0).