On October 1, 2021, after a fire had killed seven people at a hospital in Constanța, President Iohannis admitted that “the Romanian state failed in its fundamental mission to protect its citizens” (Digi24 and Presidency). On August 29, 2023, after a driver who was under the influence of drugs had killed two people at a seaside resort, Interior Minister Predoiu admitted that Romania had lost the battle against drug abuse among adults (Libertatea and G4Media). Meanwhile, a business consultant aptly commented that when individuals (or institutions) behaved consistently, their behavior could not be explained by chance alone, but the explanation needed to take account of the specific system determining that behavior (Stanciu).

This article claims that the core system underpinning Romania’s institutions has caused so many failures in various walks of life that it does not deserve to be called the rule of law; instead, a more accurate designation might be the rule o’flaw (Vrabie). Romania’s problems with the rule of law are not immediately visible, but they are all-pervasive. The state apparatus is almost always underfunded, understaffed, weak and unreliable—as well as failing to tackle inequality. Individual politicians are more part of the problem than of the solution, and they are rather failing the general requirement of public accountability . The constitutional setup and/or the political culture may need reform.

Abbreviations

| CCR | Romania’s Constitutional Court |

| CFREU | Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union |

| CoE | Council of Europe |

| CSM | Romania’s Superior Council of Magistrates (Judicial Council) |

| CSO | Civil society organization |

| CVM | European Commissions’ Cooperation and Verification Mechanism for Bulgaria and Romania |

| DIICOT | Romania’s prosecution unit specialized on organized crime and terrorism |

| DNA | Romania’s prosecution unit specialized on corruption (previously PNA) |

| EC | European Commission |

| ECHR | European Court of Human Rights |

| ECJ | European Court of Justice |

| EPPO | European Public Prosecutor’s Office |

| EU | European Union |

| GRECO | Council of Europe’s Group of States Against Corruption |

| ÎCCJ | Romania’s High Court of Cassation and Justice |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| OUG | Emergency ordinances adopted by the cabinet of ministers |

| PDL | Democratic Liberal Party, initially affiliated with the PES—Party of European Socialists, then, after 2004, with the EPP—European People’s Party; merged with the PNL in 2014 |

| PG | Prosecutor General |

| PLUS | Party (for) Liberty, Unity and Solidarity; merged with the USR in 2021, then split off in 2022 under the new name REPER (Renew Romania’s European Project); affiliated with Renew Europe/ALDE—Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe |

| PM | Prime minister, head of the cabinet |

| PNL | National Liberal Party, affiliated with the EPP since 2014, after its merger with the PDL; initially affiliated with the ALDE |

| PNRR | Romania’s post-Covid recovery and resilience plan, negotiated with the EU in 2021 |

| PSD | Social Democratic Party, affiliated with the PES |

| SIE | Romania’s external intelligence service |

| SIIJ | Special section of the Romanian prosecution department, in charge of investigating crimes committed by magistrates; reorganized and renamed SUPC in 2022 |

| SNA | Romania’s anti-corruption strategy |

| SPP | Romania’s protection service for dignitaries |

| SRI | Romania’s internal intelligence service |

| STS | Romania’s special telecommunications service |

| TEU | Treaty of the European Union |

| UDMR | Democratic Union of Hungarians in Romania, also known as RMDSZ, affiliated with the EPP |

| USR | ‘Save Romania’ Union, affiliated with Renew Europe/ALDE; merged with the PLUS in 2021 |

Current Situation

On the last Sunday in August 2023, an explosion in a fuel station close to Bucharest lead to five deaths and 57 people, among them 39 firefighters, being injured (Libertatea and HotNews). PM Ciolacu announced more rigorous inspections and controls of all fuel stations (SpotMedia). Local media examined the situation on the ground, and found out that of the 380 similar stations in Bucharest, 226 were a fire hazard (BdB). In October 2015, a fire at the Colectiv nightclub killed 64 people and injured 146 (Wikipedia). In the days following that fire, then PM Ponta also called for more inspections and controls, but to no lasting effect. Grieved and frustrated, people in 2015 took to the streets and protested against political corruption and state capture; this did not happen in 2023. PM Ponta felt compelled to resign in November 2015 (DW); in September 2023, PM Ciolacu instead proposed controversial reforms (Europa Liberă).

There is a general consensus among economists that Romania’s economy does spectacularly well, almost in spite of the government’s economic policies. A 2021 Colliers report ranked Romania 5th in the world for its evolution from 2000-20 (Economedia). At the beginning of 2023, Harvard’s Atlas of Economic Complexity ranked Romania 19th in the world, 20 positions higher than in 2000 (Adevărul). However, the executive director of a business owners’ association claims that the economy has overheated at least since 2014-17—with ‘wage-led growth’, imports, unrealistic levels of salaries and pensions (especially in the public sector), and fiscal policies not accompanied by structural reforms (Burnete).

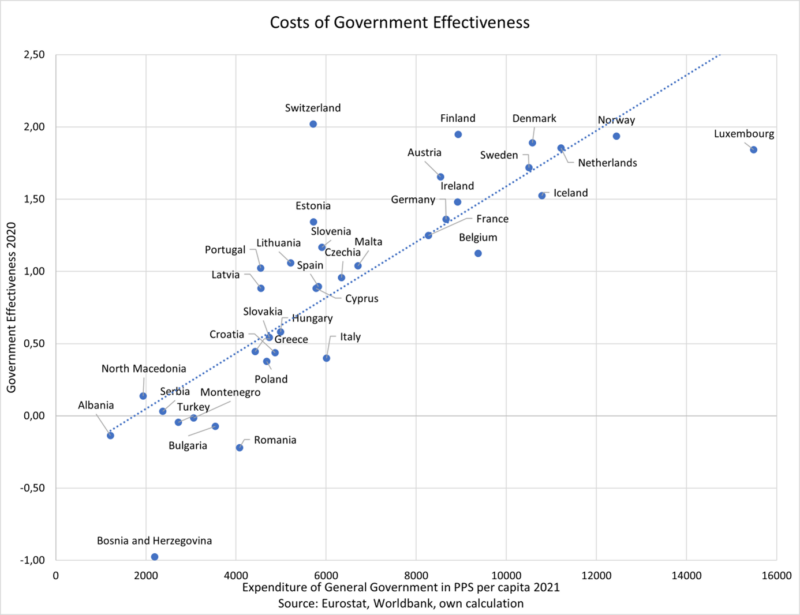

According to Finance Minister Boloș, Romania’s budget deficit has reached ~€9 bn (Digi24). Tax evasion alone causes a shortfall in budget revenues of ~€30 bn/year (Petreanu). Graph 1 shows that government effectiveness is not only poor, but also quite expensive, when compared to other countries—which reinforces the perception of corruption (see Graph 2). An alternative explanation for such poor government effectiveness points to the widespread use of discretionary powers: The Romanian government is notorious for not making evidence-based policy decisions (OECD) and for not enabling public participation in decision-making (Mitruțiu, Dilema Veche, again Burnete, and again OECD).

Graph 1. Cost of government effectiveness in Europe, 2020-21.

Source: Thomas Prorok, KDZ, August 2022.

Thus, the biggest challenges for the Romanian government relate to both the economy and the society. Romania ranks quite poorly with regard to income distribution and income inequality (Eurostat and Monitorul Social). Hence, political decisions that reinforce economic and social inequalities feed back into an emotionally charged news cycle: 69% of Romanians avoid the news (Draft Four); also, see Table 1). As a result, Romanians either turn to extremist political movements or disengage from politics altogether: Voter turnout gradually dropped to 32% in 2020 (Mediafax), while in 2023, combined support for anti-system parties rose to ~25% of those intending to vote (HotNews). Absenteeism on this scale can be partly explained by emigration—about 4 million or more Romanians simply left the country since the 1990s (OECD; also, HotNews).

Framework and Flaws

Almost all emergency situations appear to involve some rogue politician or some failure of a state institution, eroding trust in any form of justice—a judicial reform activist has concluded that law enforcement is weak and selective (Ștefan). There is very little civic involvement in decision-making, or public scrutiny thereof, and when it happens it usually takes the form of furious mass protests (see the Calendar of the Rule of Law in Romania). Not surprisingly, among all EU member states, Romania ranks at the bottom of the Economist’s Democracy Index, with an extremely low score on ‘political culture’ (Romania Insider). Romania performs similarly poorly on ‘participation’ in the Global State of Democracy indices (IDEA). Under these circumstances it is easy to understand why the Romanian government runs mostly on discretionary power. However, since public participation cannot be expected to exercise effective oversight, what other safeguards does Romania possess, in order to prevent the government’s discretion from turning into outright arbitrariness?

Tom Bingham writes in the epilogue of his 2011 book The Rule of Law that “the concept of the rule of law is not fixed for all time. Some countries do not subscribe to it fully, and some subscribe only in name, if that.” This article will not follow Bingham’s framework of 8+2 principles to analyze Romania’s rule of law, neither the six principles of the Meijers Committee (with their very technical jurisprudence review), nor the elliptical wording in Article 2 TEU, nor the extensive methodology of the EU Rule of Law Report, nor the Venice Commission’s Rule of Law Checklist (CoE). Any such approach would miss the forest for the trees, as recently observed by several journalists (Judecata de Acum and Dilema Veche). Instead, a simplified framework (inspired by all of the above) is sufficient to focus the reader’s attention on the following three specific questions:

- Does Romania have any effective constraints on the arbitrary abuse of power?

- Does Romania have a rule on how to change other rules?

- Does Romania respect human dignity?

(See B. Dima in Eastern Focus, 2019, along with S. James in The Encyclopedia of Political Thought, 2015; also, L. Sirota in Verfassungsblog, 2023; respectively, Article 1 CFREU.)

The original setup of the 1991 Constitution followed the principle that no actor should be able to capture political power in its entirety. Such a concern is understandable for a country that emerged in 1989 from more than 50 years of continuous dictatorships (fascist and communist). By design, the powers of the executive, legislature and judiciary were each internally split—in the executive, the president and the PM had different powers; in the legislature, the bicameral parliament and the constitutional court had opposing prerogatives; in the judiciary, the supreme court and the judicial council had separate jurisdictions. The 2003 amendments to the constitution introduced three significant changes:

- The CCR was no longer restricted to stopping ‘bad’ laws from coming into force, but was now also charged with resolving conflicts among the three branches of government.

- The duration of the Parliament’s and the President’s mandates were staggered (four and five years, respectively), thus imposing alternating periods of political synergy and cohabitation.

- The CSM put judges and prosecutors on an (almost) equal footing, but added political tension with the two representatives from civil society, appointed to the Council by the Senate.

The post-2003 constitutional setup created an opportunity for state capture by one of the political actors. The PSD proved to be sufficiently tenacious, even though its moves were no more than tactical, incremental adjustments; there was no strategic plan(another meaning for the flaw in the rule o’flaw). Until the early 2010s, the PNL seemed to have protected the system of checks and balances against the PSD, but it finally caved in under pressure from the third political actor: When the former President Băsescu and his former party (PDL) bent the system in their favor during 2004-14, this provoked a counter-reaction of the PNL, which joined forces with the PSD.

Each of the three significant changes to the constitution was based on good intentions but resulted in defective decisions. Taken separately, none of them would have unduly affected the constraints on the (ab)use of power; but together, they have gradually weakened the system of checks and balances: The ‘civil society representatives’ in the CSM actually function as a political prop for the governing coalition, especially against prosecutors. The staggered mandates of Parliament and President will realign in 2024, allowing a (potential) PSD-PNL alliance to grab absolute majorities (over 50%) in all election rounds (Libertatea). And among the CCR justices, there is already a majority which is set to turn a blind eye to the toxic decisions of the governing coalition.

Without effective constraints on the (ab)use of power, political corruption is ripe. Public perception of corruption has changed little over the last decade (see Graph 2). The EC’s Rule of Law Report is rather lenient when it comes to corruption (see chapter on Romania), possibly to justify the political decisions of November 2022 and September 2023, that lifted the CVM after 15 years (EC and Agerpres). Yet, GRECO is more demanding, and criticizes explicit deficiencies in Romania’s system of checks and balances (CoE). Romania’s own anti-corruption strategy fails to mention any of the constraints on the (ab)use of power, so it is not surprising that none of the public institutions feels compelled to take action (SNA). Romania’s evolution on the Rule of Law Index tends to confirm GRECO’s, rather than the EC’s findings, since Romania scores consistently below the regional average on all eight factors (WJP).

Graph 2. CPI for Romania, and relative evolution against the European average, 1997-2022.

Source: data from Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI); methodology from Piața de șpagă; caveats explained by Vrabie, January 2023.

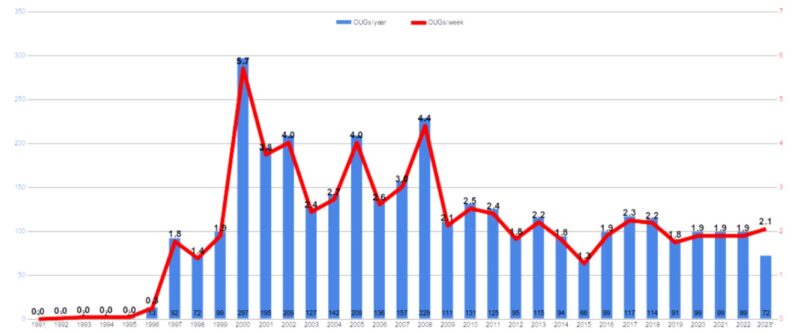

Along with the three significant changes in 2003, emergency ordinances and the ombudsman are two more constitutional features that need to be considered. OUGs were recently criticized (again) in the GRECO report (CoE), but they are a nuisance that can be traced back in time at least to the EC’s ‘to-do list’ of 2012, compiled by its former President Barroso (Euractiv). In theory, OUGs embody the principle that Parliament may delegate legislative power to the Cabinet; in practice, delegation of such power is almost unrestricted and unbound, and hence consistently abused by all Cabinets since 1997: Over the last 10 years, the country seems to have faced an average of two emergencies that required regulatory action, for every single week (see Graph 3).”.

Graph 3. Emergency ordinances (OUGs) per year, and subsequent averages per week, 1991-2023.

Source: Vrabie in Eastern Focus, 2019, updated; data from Legislative Council, capped at the end of August 2023. Note that genuine emergencies, such as the Covid pandemic or the Russian invasion in Ukraine, had no significant impact on the weekly averages in 2020-23.

Despite being adopted by the Cabinet, OUGs have the same legal power as the acts of Parliament; yet, their publication in the official journal, and subsequent coming into force, does not depend on being promulgated by the President. The ombudsman is the only institution that can prevent (or delay) the publication of OUGs in the official journal—s/he has direct and unrestricted recourse to ask the CCR for an ex-ante constitutional review. And, given that the ombudsman could be appointed or removed by the two Chambers of Parliament, s/he tends to serve the interests of the parliamentary majority that supports the Cabinet. Only in 2021 did the CCR rule that the ombudsman’s removal was not at the full discretion of Parliament (Europa Liberă).

The five elements discussed above paint a rather bleak picture of the constitutional setup: If a Cabinet has a slim majority in Parliament, the PM can still use his discretionary power through OUGs. In such a case, with the President effectively taken out of the game, the PM may try to challenge both the ombudsman and the CCR. If such a PM is skilled enough to get a couple of victories, s/he may engineer a different majority in Parliament (vote buying is not uncommon but has never been proven in the courts). In the last decade, Victor Ponta (PSD) led four cabinets, Liviu Dragnea (PSD) produced three, and Ludovic Orban (PNL) formed three more. Nicolae Ciucă (PNL) and Marcel Ciolacu (PSD) took turns at the head of two consecutive cabinets that were based roughly on the same majority (see the Calendar of the Rule of Law in Romania).

In contrast, if the PM were to enjoy a stable majority in Parliament, a supportive ombudsman, a favorable president, some influence at the CSM, and an accommodating CCR, the system of checks and balances would simply fail. It is merely an accident that Romania has never seen such a concentration of power. On average, all the cabinets formed since February 2012 lasted only 10 months, meaning that political power tends to be exercised fully only for a short time. Thus, even though Romania is quite permeable to authoritarian tendencies (Vrabie), the Romanian politicians have not yet managed to align all the necessary elements. However, an electoral alliance between the PSD and the PNL in 2024’s four rounds of elections could pose a serious threat to the rule of law (Libertatea; also, Monitorul Social). Having said this, these elections in 2024 may nonetheless be ‘safe’ because about half of Romania’s population still equates a lack of democracy with the severe poverty of the 1980s (În Centru).

Analysis and Discussion

The constitutional features reviewed above already provide answers to two of the original questions: Because of the OUGs, Romania does not really have a clear rule on how to change other rules. And, largely for the same reason, Romania does not have effective constraints on the (ab)use of power. Discretionary power is alarmingly widespread in all branches of government, and decision-makers are not in the habit of checking for the unintended consequences of their actions.

During his first mandate (2004-09), President Băsescu used his discretionary power to modify the majority in Parliament, disregarding the potential effects of infuriating the PSD. He then declared corruption a risk to national security, not considering that the SRI might gain a foothold in the judiciary. He also schemed to get a friendly majority at the CCR, which backfired in 2014, when Parliament was allowed to appoint the Cabinet Ponta III without a governing program (Digi24).

In 2012, PM Ponta of the PSD and his allies from the PNL decided on a range of actions tantamount to a coup d’état (Euractiv). The situation escalated to the point where EC president Barroso intervened, issuing PM Ponta with an 11-point ‘to-do list’ (again, Euractiv). Hence, Ponta’s power of negotiation was diminished: In 2012-13, he sought to appoint a favorable prosecutor general (Digi24), but Băsescu imposed the former PG Kövesi (2006-13) as the new chief of the DNA (2013-18).

Possibly from 2005 onwards, but documented only since 2011, SRI had signed secret protocols with the general prosecution, the judicial council, perhaps even with the supreme court. The protocols were leaked to the press in 2018, creating the impression that the SRI was engaging in widespread manipulation of criminal investigations (Curaj Înainte). Some politicians alleged that SRI and DNA may have colluded to ‘cleanse’ the political elite, yet these claims did not result in the overturning of any criminal sentences.

The SRI scandal in 2018 was preceded by two CCR rulings in 2016:

- In one ruling, the CCR banned the SRI from any involvement in criminal cases, so wiretaps and other surveillance equipment had to be handed over from the SRI to the judicial police, while the judicial police had to migrate from the interior ministry to the prosecution; none of these measures have been fully implemented to date.

- The CCR also imposed a new interpretation of the Criminal Code regarding the crime of ‘abuse of office.’ At this occasion, the DNA accused the CCR of colluding with politicians guilty of corruption, claiming that, as a result of this ruling, the state budget would lose an amount of €260 mn (Republica).

After the 2016 elections, Liviu Dragnea (PSD) and his three consecutive PMs took advantage of the situation created with regard to the DNA, SRI and CCR: Unable to become PM himself (due to his conviction for corruption in 2016, Mediafax), Dragnea created a narrative about the ‘deep state’ that put politicians in prison, and unleashed a political process with the aim to eliminate judicial control over the executive: changes to three laws on the judiciary, changes to the Criminal Codes, and the removal of Kövesi from the DNA.

As a result, the CSM since 2017-18 no longer works in plenum, but instead in two separate sections, which diminishes the magistrate status of the prosecutors (Venice Commission, 2018 and 2022) and undermines the judges’ independence (Chiș). The SIIJ was meant to counterbalance the DNA—in theory, the SIIJ would prosecute crimes committed by magistrates; in practice, it persecuted magistrates that put politicians behind bars. Though the SIIJ now allows the statute of limitations to let cases wither away (Digi24, RFI and Europa Liberă), magistrates are still not safe from politicians.

With a different majority, the CCR changed the statute of limitations with two rulings in 2018 and 2022. In essence, the Code of Criminal Procedure now only grants a very short period of time for the discovery of a crime, the investigation, indictment, trial, appeal, recourse, conviction, and the enforcement of the court’s judgment. Most affected by these changes are complex cases of fraud and corruption that involve politicians (Judecata de Acum). There is obviously no incentive for Parliament to legislate for more protection of the prosecution.

While the rule of law does not rely solely on the prosecutors, the political decisions taken in 2017-18 (the three laws on the judiciary, the CSM and SIIJ, the statute of limitations and Kövesi’s removal) had a chilling effect on the judiciary (FJR and Funky Citizens): Politicians hold just enough discretionary power to always be able to subdue the judiciary, in spite of international safeguards for the rule of law. And the major political parties (especially the PSD and the PNL) maintain the view that there should be no restraints on the exercise of political power.

Kövesi’s successful candidature in October 2019 to head the EPPO was not enough to ’avenge’ the Romanian magistrates against their own politicians. Instead, her removal from the DNA in 2018 (HotNews) had the unintended consequence of creating more discretionary power: Due to a combination of the following three judicial decisions at European level, Romanian judges may extend their adjudication beyond the legal restrictions laid down in the procedural code:

- In 2020, the ECHR convicted Romania for not overturning an unlawful decision to remove a chief prosecutor and for not taking any measures to prevent such an abuse of power in the future (Europa Liberă).

- In 2022, the ECJ reviewed a case involving the SIIJ and the CSM, and decided that judges may disregard CCR decisions that contravene EU law (also, Europa Liberă).

- In 2023, once again, the ECJ ruled again that judges may disregard CCR decisions concerning the statute of limitations in cases of fraud and corruption (G4Media and HotNews).

The landscape of discretionary power described above is bound to also impact human rights. Table 1 paints a dark picture of a society affected by systemic violence, and the effects of this are very serious for the Roma (and Hungarian) minority (CRJ), some religious minorities (Să fie lumină), the LGBT+ community (Monitorul Social), for immigrants (Recorder and Digi24), the disabled (CRJ), and for women and young people/children in general (Filia and Eurostat). The ombudsman should play a key role, but this institution is more valued for its role regarding OUGs than for protecting human rights and dignity. Not even the CCR shows concern for protecting human rights and/or human dignity (V. Perju in Dima & Perju, 2023).

Where the ombudsman and other authorities fail to protect human dignity, CSOs intervene. But the government loathes the high esteem in which the CSOs are held by international organizations and has repeatedly attempted to silence them. Civic activists suffered most during the Dragnea Cabinets, but PM Ciolacu’s legislative package from September 2023 aims at diverting sponsorship funds in order to cover the budget deficit (G4Media). One of the (potentially) most affected CSOs is currently building the first new hospital in Romania in more than 30 years, while the Cabinet recently rejected €740 mn from the PNRR earmarked for health infrastructure (Economedia).

The ‘referendum for the family’ of 2018 illustrates the interplay between human rights and discretionary power: Voter turnout failed to reach the validation threshold, as the referendum was silently boycotted by society (DW). But the CCR’s interpretation, that marriage unites a man and a woman, is still legally valid, even if the term used in the Constitution (art. 48) is ‘spouses’. Also, in spite of an ECJ ruling in 2018 (Curia), Romania still offers no protection to LGBT+ couples, a finding which was confirmed by a judgment of the ECHR in 2023 (ECHR). Instead of complying with the decisions of the European courts, Romania played the traditionalist card, and appealed against the ruling (G4Media).

Disregard for human dignity peaked during the Covid pandemic. President Iohannis, along with PM Orban and the CCR majority, supported a resurgence of the secret services (and the military): Early in 2020, Romania notified a derogation from the European Convention on Human Rights (HotNews), effectively classifying all decisions and procurements related to managing the health crisis (Rise Project). As a result, ‘essential personnel’ and government cronies were prioritized over ordinary citizens and even medical staff from the start of the vaccination campaign in 2021 (SpotMedia).

Throughout the pandemic, the STS (secret service in charge of communications) increased its influence. The STS started with the vaccination platform, but gradually expanded into other areas of central administration, with ‘infrastructure support for digitalization’ alongside the SRI and the SIE, with the SPP also possibly involved. Only one Romanian CSO specializes on legal and civic scrutiny of cyber-security (ApTI), and this organization can barely keep up with all the changes, both domestic and European (Context). The government’s discretionary power, once again, has created more unintended consequences.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the military and secret services seem to have a stronger influence on decision-making. As PM Ciucă (2021-23) was a retired general, the Romanian government recently adopted a security narrative that enforces two opposing, but excessive and costly attitudes among dignitaries and civil servants: Either “I’m afraid of making (the right) decisions, because law enforcement is discretionary and will crush me” or “I’m not afraid of making (even illegal) decisions, because law enforcement is discretionary and won’t touch me” (Judecata de Acum). These attitudes and the underlying notion of ‘selective impunity’ illustrate how ineffective the prosecution has become in recent years (especially the DNA and the DIICOT).

Both attitudes are widespread among the three branches of government, and can be traced back to more discretionary decisions that never considered their unintended consequences:

- Since 2015, when Parliament reformed the law on party financing, state subsidies for political parties have increased dramatically from ~€1.2 to ~€50 mn/year, with 57% of that money going to the media and advertising (Expert Forum). As a result, media outlets have turned into propaganda machines, and the capacity for public scrutiny has been diverted towards identifying mis- and disinformation, rather than focusing on government effectiveness.

- Also in 2015, when Parliament reformed the election laws, political parties received an electoral bonus for incumbents at all levels of government (Politică fără Bariere). Combined with the toxic effects of subsidies for the media, this lead to political parties now attracting talking heads and imposters, rather than people capable of developing policies. Political leadership is now warped in favor of decisions that retain hard-core voters and repel the undecided (DoR).

Adding insult to injury, the legal framework allows political parties to get a subsidy bonus for female candidates in safe seats on the party lists. However, no repayment of the bonus is required should the female candidates resign. As a consequence, internal party strategies, especially at a local level, ‘encourage’ women to resign from their elected positions in favor of male candidates placed lower on the list (Vrabie; also, FES). Not only are women underrepresented in politics (Expert Forum), but such behavior effectively prevents decisions which would serve their interests (Filia).

The plethora of bad decisions presented above calls into question the actual competencies of Romania’s politicians. This question was debated for some time (the Calendar of the Rule of Law in Romania, Șercan and Nicolae), but not even President Iohannis agreed to a 2015 civil society request to introduce integrity and competency criteria for ministers (Mediafax). The regrettable downside of this failure is that the PSD and the PNL gradually turned illiberal ‘by mistake’ (Vrabie): Their lack of integrity compels them to cover up their mistakes, rather than be accountable; and the decisions covering up the mistakes are additional mistakes that create a vicious circle of anti-accountability.

Conclusions

The systemic flaws of the constitutional text allow for widespread discretionary power across all branches of the Romanian government. OUGs effectively prevent the existence, or enforcement, of any rule on how to change other rules. In addition to the OUGs, the interplay among high-level institutions in the three branches of government has increasingly weakened any constraints on the arbitrary (ab)use of power. In fact, the two major parties currently governing together (PSD and PNL) take the view that there should be no restraints on the exercise of political power. The only political objective that seems to make them show some restraint is the commitment to OECD accession, presented as “a rules-based international order” (OECD).

With OUGs so frequent (see Graph 3) and discretionary power so widespread, the government makes decisions that show no respect for human dignity. Either due to corruption (Graph 2) or mere incompetence, government effectiveness in Romania is poorer and more expensive than in the neighboring countries (Graph 1). The dissolution of the system of checks and balances (especially of the judiciary in 2017-22) turned Romania into an attractive place for all sorts of scoundrels (see the brothers Tate at BBC, in Table 1). Coming full circle on discretionary power and disrespect for human dignity, Romania in 2022 received the highest number of ECHR convictions for inhumane and degrading treatments of all EU member states (Europa Liberă). It follows that, while the judiciary ought to keep checks on the exercise of political power, the magistrates themselves are not blameless either.

While most analysts consider the PSD to be the villain in the story of Romania’s rule o’flaw, the sequence of decisions and political choices in 2012-23 can also be interpreted differently: The PSD (and its allies) did not have a strategic plan; instead, they responded to their environment with tactical and incremental adjustments. The PSD was just tenacious in pursuing its agenda, and clever at sharing power with the PNL—the rational choice for taking advantage of the four rounds of elections to be held in 2024. Only time can tell whether this latest maneuver will work in their favor or if the next crisis will set the system on fire. If the next political regime can bypass the constraints to exercising political power, as well as the rule on how to change other rules, Romania might fall prey to state capture, which will also have dire effects on human dignity.

The latest GRECO report advises that Romania should fix the fundamental problem of emergency ordinances (OUGs); the OECD has a similar request. The best course of action would be an amendment to the Constitution, but politicians will not easily agree to abandon their favorite ‘toy’. There are no incentives for political parties to improve their selection of candidates either—in spite of civil society demanding that competency and integrity should be the ultimate criteria. Under these circumstances, the key institutions are the CCR and the ombudsman, should they choose to assume bigger (or higher-order) responsibilities. Constitutionally, they are the only players that can restrain the (ab)use of power, enforce the fundamental rules of political decision-making, and restore respect for human dignity.

Author Note

Codru Vrabie is an independent activist, trainer and consultant on matters of good governance, with a focus on judicial and administrative reforms. Codru has worked with a variety of civil society organizations since 1998, but is no longer affiliated with any CSO since 2020. He wrote this article for Kultura Liberalna/Let Law Rule as a sequel to his cooperation with GlobalFocus Centre. Since 2010, Codru has been an external contractor for the Rule of Law Programme South-East Europe at the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung and has worked as one of the trainers in the Leaders for Justice Program. In 2021, he hosted the podcast Rule of Law Rules (in Romanian), produced by KAS/RLPSEE.

Codru Vrabie extends his gratitude to Oana Popescu-Zamfir, Radostina Pavlova, Doru Toma and especially Cristian Lupșa for their help in editing and polishing the final version of this article. All the information in this article was current at the time of writing, in September-October 2023.

Table 1.

| Date & Source | Subject matter |

| Jul. 6, 2023 CIM & BdB | DIICOT investigates a case of organized crime related to several healthcare centers in Voluntari, near Bucharest, where elderly and disabled persons were ‘cared for’ in appalling conditions, leading to the arrest of 24 people. The owners of the centers had received state subsidies for healthcare, benefiting from political protection. The case was initially called “Cristina’s camps” (a direct reference to the concentration camps), then “Ilfov camps” (due to their location in Ilfov county), and later became the “healthcare horror” scandal. |

| Jul. 10, 2023 CIM & BdB | A series of articles dubbed “they all knew” exposes the network of public institutions and political figures that were supposed to act in the “healthcare horror” scandal but chose to ignore the situation, months before the original article was published in February. The most prominent political figures identified are the Labor Minister Budăi, the Family Minister Firea, and the mayor of Voluntari. |

| Jul. 13, 2023 HotNews | Labor Minister Marius Budăi resigns because of the “healthcare horror” scandal. He claims the responsibility lies with the local and county authorities that have jurisdiction over Voluntari, but fails to mentionthat he had decided in April to ban all impromptu civil society inspections at the healthcare centers. |

| Jul. 14, 2023 HotNews | Family Minister Gabriela Firea resigns from all political positions, except for her post as senator. She claims the “healthcare horror” scandal has been orchestrated to block her candidacy as mayor of Bucharest in the local elections in the fall of 2024. She also denies any connection with the healthcare centers of Voluntari, where her husband is the current mayor. |

| Jul. 24, 2023 CluJust & PressHub | ÎCCJ and CSM reinstate a judge after 9 years, confirming the statute of limitation for the criminal offence of receiving a bribe. She had initially been sentenced to 7 years in prison, but the interplay of appeals and exceptions raised with various courts lead to her not serving any time in prison. Upon her reinstatement, she is not only appointed to lead the civil section of the Constanța Tribunal but also receives salary back payments amounting to about €600,000. |

| Jul. 27, 2023 Europa Liberă | ÎCCJ acquits former Securitate officers that may have ordered the torture and killing of anti-communist dissident Gheorghe Ursu in 1985. While the verdict may be legally sound, the arguments put forth by the 3-judge panel demonstrate a serious failure to acknowledge the evils of the communist dictatorship and to distinguish between right and wrong in recent history. |

| Jul. 28, 2023 Pro-TV | Close to Tg. Mureș, an impromptu inspection by civil society activists discovers 7 people in the basement of a healthcare facility. 13 people are immediately removed from the premises and taken to a nearby hospital. The case occurs less than 1 month after the “healthcare horror” scandal, and 2 days after the facility had been inspected officially. |

| Jul. 31, 2023 Pro-TV | In Urziceni, a young woman gives birth on the sidewalk in front of the hospital, because its only obstetrics doctor cannot cover all the shifts; a Roma rights activist denounces racism and discrimination (Investigatoria). |

| Aug. 8, 2023 Agerpres | Former chiefs of the riot police are indicted for abuse of office related to the street protests of 10 Aug. 2018, when 300+ people were injured while speaking out against the Dragnea regime and PM Dăncilă’s cabinet. The DW deplores that not all culprits are included in the indictment, notably not those responsible politically. |

| Aug. 8, 2023 HotNews | At the end of a music festival in Cluj, the riot police fines an artist for profanity and disturbing the peace, and presses charges against him at the anti-discrimination council. |

| Aug. 16, 2023 Adevărul | At a seaside resort, tourists get into a fist-fight with lifeguards over red- and yellow-flag restrictions to swimming. Four individuals die while attempting to save children from drowning. |

| Aug. 21, 2023 Republica | An old informer who had collaborated with the former Securitate (secret police of the communist regime) receives an honorable funeral and praise, in spite of him (allegedly) having contributed to the 1988 killing of a former director of Radio Free Europe. |

| Aug. 22, 2023 G4Media | A young woman dies in the hospital of Botoșani, gasping for air, after suffering a spontaneous miscarriage, because the doctors there did not have a medical protocol in place to deal with such a situation. |

| Aug. 23, 2023 BBC | Evidence from Romanian prosecutors exposes sexual violence and mental coercion against women by former kickboxers now charged with rape and human trafficking. |

| Aug. 24, 2023 Libertatea | At the 2 May seaside resort, a nouveau-riche young man driving under the influence of drugs kills two teenagers, because the traffic police has no equipment and no protocol for preventing abuse of alcohol and/or drugs. |

| Aug. 26, 2023 G4Media | The government seeks to reverse the ECHR decision of May, whereby Romania was convicted for not yet adopting legislation recognizing and offering legal protection to same-sex couples or families (note that a referendum attempting to ban same-sex marriage failed in October 2018; however, a CCR decision from September 2018 allows the interpretation that same-sex couples can only have access to a common-law union, and not marriage). |

| Aug. 28, 2023 Libertatea | Vice-minister of the Economy Lucian Rus admits that consultations on Romania’s ‘new’ tourism strategy started with a document drafted in 2018. Sources from the ministry point out that the World Bank has helped with the original document, but the ministry has ignored it for 5 years. |

| Aug. 28, 2023 PressHub | Newly appointed Family Minister Natalia Intotero attacks civil society representatives at a public consultation on child protection; she claims that impromptu civil society inspections in childcare centers are prohibited by GDPR. The situation is almost identical to what happened in April at the ministry of labor (see above details about the “healthcare horror” scandal; also, IPPF). |

| Aug. 29, 2023 Digi24 | Finance Minister Marcel Boloș claims that expenditure for Ukrainian refugees has affected the budget deficit. Context proves that EU money (~€1.5 mn) earmarked for their food and lodging has not been spent, and that ~25,000 refugees have been forced to leave the country. |

| Aug. 29, 2023 G4Media | In the aftermath of the 2 Mai resort case, Interior Minister Cătălin Predoiu declares that Romania has lost the battle against illegal drugs among adults. He proposes to tackle drug abuse among minors, but effectively refuses to accept responsibility and instead blames parents and schools. |

Codru Vrabie, GlobalFocus Center