Even though the era filled with the scandals of Mr Babiš may have ended, it does not mean that the reforms are not needed anymore. The new government has to pass important changes that would prevent state capture and improve the socio-economic situation of marginalised groups.

- There are several critical aspects that undermine trust in the state of rule of law in the Czech Republic. Although the Czech Republic has relatively strong and stable constitutional checks – in particular the Senate and the Constitutional Court – there are still some alarming challenges to the rule of law, some of which have become apparent since the ascension of Andrej Babiš to the governmental office.

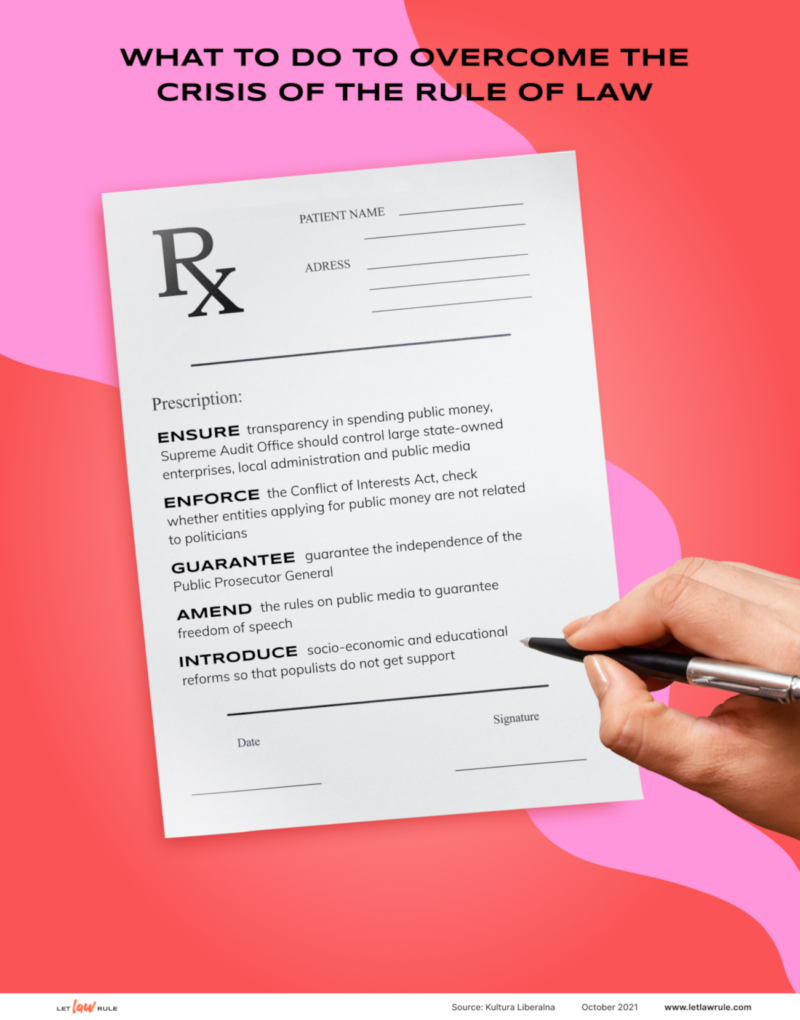

- It is clear that there is a lot to be done to improve the situation in Czechia: to secure more transparency in management and distribution of public money, to strengthen the conflict of interest act and its enforceability, and to amend laws in order to guarantee greater independence of top public prosecutor and publicly owned media.

- Furthermore, important socio-economic and educational reforms have to be implemented to tackle problems that are at the root of support for populist political voices. Creation of healthy information spaces for public discourse should also be secured.

Prevention of the Conflict of Interests

One of the big challenges for the Czech Republic emanating from the participation of Andrej Babiš in the government is the issue of dealing with his conflict of interests. After the passing of the Amendment of the Conflict of Interests Act in 2016, which included provisions that made it illegal for a company owned by a Czech minister to receive subsidies, state investment incentives, and public contracts, or to operate television and radio broadcasting and publish periodicals, Babiš, the owner of the Agrofert Group (conglomerate holding company, which operates agriculture, food, chemical, construction, logistics, forestry, energy and mass media industries) and then Minister of Finance, decided to move his holding to trust funds, claiming he followed the newly amended Conflict of Interests Act and resolved his conflict of interests.

However, even after the transfer of his company to trust funds, voices of doubt appeared, saying that Babiš had not cut his ties with Agrofert and still maintains influence on the conglomerate’s decision making. The EU institutions noticed and started an investigation, and the European Commission concluded in an audit released in April 2021 that Prime Minister Babiš had a conflict of interest as final owner of a business empire, mainly under the Agrofert group of companies, that receives EU funding. The Commission later announced that it would halt the payment of some EU subsidies until the country tightens its laws to guard against conflicts of interest.The era of the rule by Andrej Babiš and his ANO movement raised awareness in the country about the issue of “state capture” – concern that private interests significantly influence a state’s decision-making processes to their own advantage. There is a fear that Czech ministries led by ministers nominated by ANO have not done enough to properly deal with the conflict of interests controversy and rather than protecting public resources they defend the interests of one specific private entity. It is presumed that state institutions do not necessarily act in favour of the Prime Minister on his direct orders, but they attempt to surmise their superiors’ wishes and act without explicit directions. Given this state of affairs, systemic changes need to be implemented in order to effectively reduce the risk of state capture in the Czech Republic.

Firstly, the Conflict of Interests Act should be properly enforced by state institutions. It is necessary to strengthen the standards and methods of Czech ministries in uncovering ownership structures of entities which apply for public money (subsidies, public procurement or investment incentives). Establishment of the Register of Ultimate Beneficial Owners was a good step, but it needs improvement and public entities cannot fully rely on the data it contains and they need to verify information on ownership structures of companies to prevent the conflict of interests and transfers of public money to companies that are not fully transparent.

Secondly, an amendment to the Conflict of Interests Act should be considered. The enduring debate on the prime minister’s conflict of interest should lead to evaluation of the existing legislation. For instance, limitations for government ministers could include not only not owning media or a certain percentage of shares in a company, but also ultimate beneficial ownership of these entities. The extent of sanctions could be expanded as well.

Thirdly, the reform of public administration needs to be promoted. The Czech Civil Service Act has been problematically amended several times and does not provide enough guarantees for preservation of independence of bureaucracy. A new amendment, which would find proper balance between political and bureaucratic spheres, has to be prepared in order to prevent politicisation of public administration and to secure a stable source of expertise for public policy-making.

Part of the reform of public administration and the Conflict of Interests Act should also tackle the revolving door problem with establishment of a “cooling-off period”. This is almost non-existent in the Czech legal code, so there is no control mechanism for a situation when a high positioned public office holder leaves office but continues to gain significant benefits through their informal political influence and contacts.

Strengthening of the Independence of the Prosecutor General

One of the main weaknesses of the Act on Prosecutors is the lack of sufficient institutional independence of the Prosecutor General, since the top prosecutor can be dismissed by the government anytime, without reason. This major flaw in the system became more obvious when former Prosecutor General Pavel Zeman evaluated the decision by the Metropolitan Public Prosecutor’s Office in Prague to stop the criminal investigation of the Prime Minister Babiš, regarding the financing of Stork’s Nest, a resort in Central Bohemia for which Babiš is alleged to have illegally acquired 2 million Euros of EU subsidies intended for small companies. Mr. Zeman eventually quashed the decision and ordered an additional inquiry into the case. Nevertheless, he was in a highly uncomfortable situation, deciding on the future of criminal investigation of the prime minister, whose government could dismiss Mr. Zeman any time.

In order to ensure a more independent role for the Prosecutor General, a change in the law is needed. As GRECO also recommended, reform of the procedures for the appointment and dismissal of the Prosecutor General and other chief public prosecutors is necessary, in particular by ensuring a) that any decisions in those procedures are well-reasoned, based on clear and objective criteria and can be appealed to in a court; b) that appointment decisions are based on mandatory, transparent selection procedures and; c) that dismissal is possible only in the context of disciplinary proceedings.

Reform of Czech Media Laws

In the Czech Republic, there are four publicly owned media institutions: Czech Television, Czech Radio, Czech News Agency, and the Council for Radio and Television Broadcasting. Each of these institutions is overseen by its council, which is politically appointed (elected by the Parliament). This is governed by largely out-dated laws, which means that public service media are not sufficiently protected from political influence and that private broadcasting media are weakly regulated with regard to their impartiality and plurality.

In particular, Czech TV has been under frequent attack by some populist politicians, including president Zeman. In recent years, several controversial candidates, deeply critical of publicly owned media, were chosen as members of the Czech Television Council. This is despite – or, arguably, because –Czech Television enjoys high credibility and impartiality ratings among the populace. There is also on-going concern that certain politicians are attempting to pressure on Czech TV through these council members in order to shape reporting by the television. The media laws should be amended in order to strengthen the independence of public media. One of the ways to achieve a higher standard of media councils is to set better criteria for candidates, and for organisations which nominate candidates. Another change which could contribute to less politicisation of these control bodies would be the sharing of the election process between both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate – e.g. one half of the members of a council would be voted by one chamber, the other half by second chamber.

As far as management of financial resources by Czech TV and Czech Radio – which are often the target of criticism by politicians – is concerned, the oversight should be entrusted to a respected independent authority, the Supreme Audit Office. This again needs a legislative change in the form of the long debated extension of powers of the Supreme Audit Office.

The steady decrease in the plurality of private media is also a concern. There are currently several major media conglomerates that operate cross-media portfolios of televisions, radio, print, and online news. The largest of them, which reaches some 68 % of the population each week, is owned by Prime Minister Babiš’s Agrofert holding. There are no effective mechanisms to guarantee that these media are not exploited by their owners, who want to further their political interests. This situation could be improved by strengthening the currently weak professional self-regulation of journalists, supporting the adoption of a more ethics-focused working culture at media firms, reforming the state broadcasting regulator, and limiting cross-media ownership.

Accountable and Transparent Governance

Despite the Babiš government’s declared focus on fighting political corruption, there has been only limited progress in making governance more transparent and accountable. In fact, some of the proposed measures have been in a parliamentary limbo for multiple election terms. This is despite the fact that these measures respond to common and publicly perceived problems of the Czech public administration.

The first problem is the limited scope of oversight of how public money is used. This is particularly true for state owned enterprises. Among these are, for example, the biggest electricity producer in the country, ČEZ, and Prague airport. Despite the fact that these are major businesses and employ up to tens of thousands of people, they are out of reach of the Supreme Audit Office. Reforms should ensure that these enterprises are accountable not only to conduct themselves lawfully, but also efficiently, effectively, and economically.

However, state owned enterprises are not the only category of public finance that is missing from the Supreme Audit Office’s scope – local administrations and public service media should be included as well, with care being taken to balance the sometimes conflicting interests of accountability and minimising bureaucratic burden.

The Czech Republic also missed an opportunity to be a pioneer with regard to the protection of whistle-blowers. A well-drafted bill that would protect those who reveal corruption from revenge by higher-ups has been presented, but it has failed to be adopted in Parliament and the country is currently likely miss the transposition deadline of a related EU directive.

Non-transparent lobbying is yet another threat to good governance. Lobbying is commonly perceived as immoral or even illegal due to the association of the term with perpetrators of bribery and public contract manipulation. A general scepticism and misunderstanding of what lobbying is may thus be one reason for the current reluctance to differentiate between legitimate and corrupt instances of it. A bill that would introduce a register of lobbyists and lobbying contacts would help more easily distinguish between corruption, clientelism, and the legitimate defence of citizens’ interests. Such a bill has been proposed but was not debated before the parliamentary term ran out.

Countering socio-economic drivers of mistrust in democracy

Studies have shown trust in democracy to be strongly associated with economic standing and social capital. People, who have experienced social crises such as unemployment, poverty, or loss of housing, have less trust in democracy and that this may lead to support of political parties with illiberal or authoritarian tendencies.

A long-standing issue is over-indebtedness. Over 7 % of the population are facing court-ordered debt enforcement, and over 5 % have 3 or more such orders. In the socially most at-risk regions, in the northwest of the country, more than 16 % of the population is facing court orders due to debt. These people find themselves in debt traps, often due to some form of financial exploitation, such as predatory loans. They are then driven towards the unregulated grey economy. Naturally, the real effect is even significantly more widespread than that, as an individual’s debt often severely impacts their family.

There have been recent improvements to law governing enforcement procedures, but these changes have been disappointingly piecemeal, largely due to the strong lobby of those for whom the current system benefits: debt enforcers, creditors, and some law firms. The recent changes help by setting a maximum duration of enforcement, ending the enforcement of old debts from the largely unregulated times following the economic transformation of the 1990s. The recent changes also mean that the debtor’s payments will be put towards the principal debt first, and only after that towards accessories, such as the cost of enforcement. This means that debtors will no longer find themselves in a stalemate where they keep paying and the debts keep increasing still due to interest.

However, some of the most hotly anticipated improvements to the system have not yet been legislated. The first is the territoriality of enforcers. This would stop creditors from selecting enforcers located far from debtors, which means reducing enforcement costs for the debtor. Another improvement would be the principle of 1 debtor, 1 enforcer. Currently, different creditors of the same debtors can each utilise their own enforcer, thus leading to the multiplication of the enforcement costs. Both of these problems also make enforcement and extremely competitive markets. Furthermore, since it also operates on fixed prices, this competition often takes the form of enforcers willing to operate on razor’s edge of legality.

Furthermore, the current system of debt relief and personal bankruptcy is very unforgiving. People enrolled in debt relief have to survive on a very low ‘unseizable minimum’ while having no certainty that their debts will be cancelled, which is reliant on a court judging the subjective criterion of whether the debtor ‘gave their maximal effort to pay’.

Legislating the changes presented above would improve the socio-economic situation in the most of the affected regions, lower the present pressure on the welfare safety net, and improve trust in democracy and public administration.

Modern education that supports resilient democracy

Citizens who have achieved a lower level of education are more likely to mistrust rule of law and democratic institutions. Furthermore, the Czech Republic faces a high level of generational reproduction of education levels, meaning a child whose parents only achieved elementary education is far less likely to attend university than a child with university-educated parents.

In more theoretical terms, we can differentiate between a general and a specific type of political trust. While specific trust is related to known and familiar actors, general trust entails trust in unknown actors through confidence in the norms of a shared political space. Illiberal and populist actors benefit from a lower general trust, which they prefer to replace with specific trust (and because general trust in a system with which they find themselves at odds with would lead to their exclusion from the political mainstream). Education in particular can be a powerful tool to support the general trust in rule of law based democracy. This is demonstrated by the significant difference in trust levels towards democratic institutions such as civil society NGOs between seniors (who were educated during the communist regime) and youth.

Despite its importance, the Czech schooling system is generally seen as relatively lacklustre and, according to UNICEF, the quality of schools greatly varies, furthering inequalities. A good number of expert proposals to improve education have already been devised. These range from improving processes for formulating education programmes through digitalisation and support for teachers, to inclusivity.

The quality of education programmes should be enhanced by establishing a middle level of governance between the ministry and individual schools, which would ensure effective sharing of information, local cooperation, and expertise. Verification of the results of education could be improved by clarifying the competencies of, and increasing formal requirements on, institutions tasked with creating standardised tests.

Greater inclusivity of the schooling system would be ensured by establishing professions that support teachers, such as school psychologists, social workers, etc. The existing lifelong learning programme should also be significantly expanded.

The teaching profession can be made more attractive to good candidates by creating professional standards and matching training and financing for teachers. Likewise, reform of teacher education and support for young teachers is also vital.

Lastly, the school system needs to embrace digitisation. This is due to the fact accessible data is crucial to evidence-based policy, and because digitisation can reduce administrative burden on teachers.

Healthy information spaces for public discourse

Fake news, hoaxes, and the generally poor quality of public debate present an escalating threat to the rule of law. Disinformation comes from many sources, including foreign interference, populism, political extremism. This long-term threat has been particularly powerful during the COVID pandemic, as misinformation has weakened the public health response and immunisation rates. An environment in which disinformation thrives is also an environment where politicians find it more difficult to present complex solutions to complex problems, strengthening populists who present themselves as saviours.

However, disinformation is only one side of the threat to an increasingly online society. Unregulated digital platforms create limits to freedom of expression that are non-transparent and led by commercial interests. In order to escape criticism for propagating fake news, delete content in a more wholesale manner is often the easiest solution for digital platforms, thus often taking legitimate speech along with it.

The task that the country currently faces in terms of safe and open circulation of information is to balance the threat of fake news with protection of freedom of expression. This is, of course, a task to be tackled at both a European and national level, as Czechia can scarcely influence technological giants. While the debate surrounding freedom of speech is often ideological to the point of dispensing with practical solutions for content-moderating processes, there is a wide consensus on some of the most general priorities.

Legal rules are needed to define situations in which executive power can interfere with freedom of speech, and under what conditions. A similar situation to how some public offices demanded online platforms to take down COVID related fake news without having any support in relevant laws should be avoided. A process should be devised to establish proportionality between different public interests and freedom of speech in administrative decision-making.

Rules should also be put in place for digital platforms. These include a wide variety of organizations ranging from social media through online marketplaces and application stores to video and file sharing sites. Potential rules fall into two areas. The first is procedural – users should have the right to report harmful content and should also have a right to fair and timely review of reported content. This type of rule is likely to be created on a European level. The other type of rule is more controversial and so it needs to be matched to national perceptions and culture. These rules deal with what information is deemed to be unlawful and whether the removal of legitimate speech from online platforms should be punishable (for example as a tort or even a crime). Furthermore, it should be ensured that the ‘illegal offline = illegal online’ principle is observed and that the law is more consistently enforced online. A part of this is the establishment of predictable sanctions.

Regional inequalities and the perception of political powerlessness

Czech Republic is a country with long-standing and significant regional differences. These differences have been shaped through a tumultuous historical process. In the latter half of the 20th century in particular, heavy industry such as coal mining, the petrochemical industry, and the steel industry have come to define some border-adjacent regions of the country, particularly in the northeast and northwest. As these industries – as well as some light industries, such as textile manufacturing – face stiff global competition, often unsuccessfully, these regions have fallen into many problems. Social exclusion, low education levels, low income, and low social capital are all factors feed into a general mistrust in institutions and generate support for populists. Citizens in these regions often do not feel represented by the political process and perceive a rift between themselves and the much richer and selfish Prague.

Among some of the solutions to rectify this situation is moving some parts of the public administration out of Prague and into the regions and supporting regional development, including education and healthcare. Technological and business innovation would also help replace faltering industries.

A new challenge for these regions will be presented by decarbonisation. Particular care should be taken to ensure requalification and employment opportunities for citizens affected by the end of coal mining and by transition to clean energy and alternative modes of transport (due to the importance of the automotive industry to the Czech economy).

Conclusion

The challenges to the rule of law in the Czech Republic are clear. Although there are several important constitutional checks that prevent radical overhaul of the democratic system, there is no guarantee that the situation will not deteriorate. There are fragile areas in society that could potentially crumble if much needed socio-economic and administrative reforms are not implemented. Although the Czech rule of law is in comparatively better shape than in some other Central and Eastern European countries, civil society has to be ready to defend possible attacks on fundamental rights and freedoms. In this respect, there is hope in the engagement of a strong non-governmental sector and active citizens, whose voices can be regularly heard in public discourse.

The wave of optimism on the future of the rule of law and illiberal populism in the Czech Republic prevailed right after the general elections in October 2021. Unexpectedly, the incumbent populist billionaire prime minister, Andrej Babiš was defeated, and moderate centre-right parties received a clear parliamentary majority. Even though the era filled with the scandals of Mr Babiš may have ended, it does not mean that the above-mentioned reforms are not needed anymore. On the contrary, the new government has to pass important changes that would prevent state capture and improve the socio-economic situation of marginalised groups that tend to look up to anti-systemic political voices. If the newly formed political leadership does not use this opportunity, the next elections could bring illiberal politicians to power again.

Lukáš Kraus, Miroslav Crha

* Photo: Demonstration at Old Town Square, Prague – Demonstration for independent justice (Demonstrace za nezávislou justici / Demonstrace za nezávislost justice) anti Marie Benešová and Andrej Babiš, May 2019, author: Martin2035. Source: Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 4.0).