Fidesz demolished the institutions established in 1989-1990 and significantly weakened institutions designed to balance the executive power. Similar things have occurred in the field of freedom of speech and media.

- Fidesz demolished the institutions established in 1989-1990 and significantly weakened institutions designed to balance the executive power. Similar things have occurred in the field of freedom of speech and media.

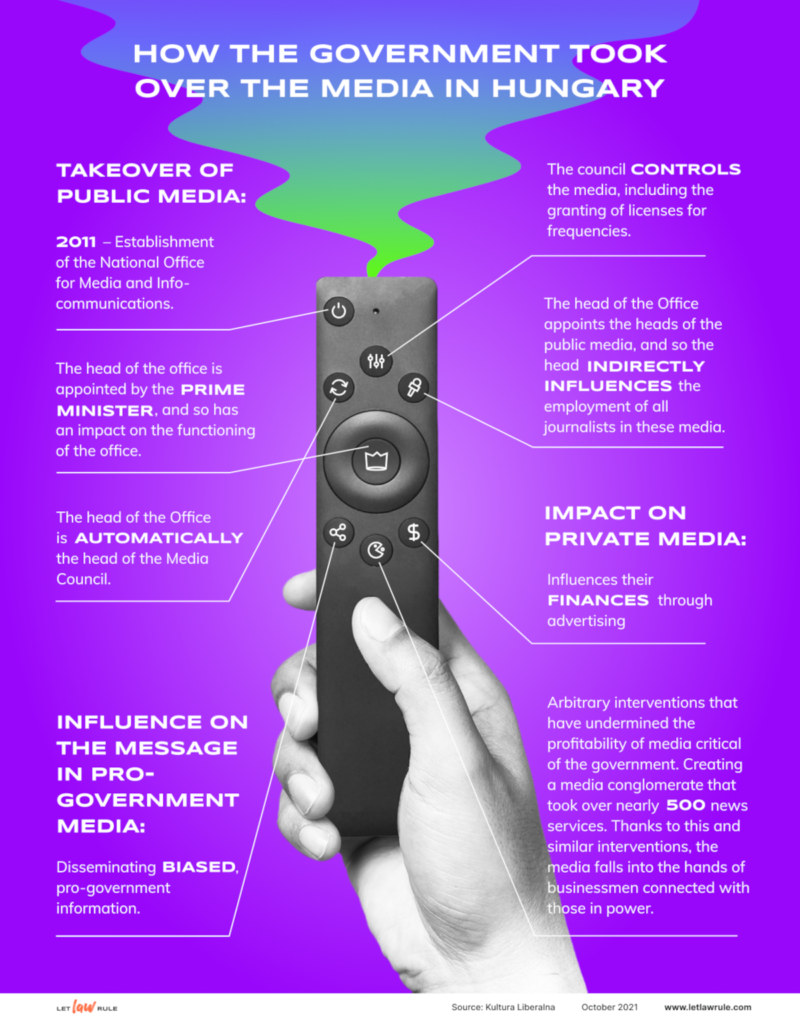

- The Fundamental Law facilitated the de jure takeover of public media and de facto takeover of private media outlets. Based on these constitutional provisions, the ruling majority undermined the independence of the authorities responsible for overseeing private and public media, controlled access to public information, and manipulated the media and the advertising market.

- Public media is managed by the National Media and Info-communications Office, whose head is appointed by the Prime Minister. Private, pro-government media presents biased information, whilst independent media have been weakened or destroyed by state financial intervention.

- Non-governmental organisations became the next goal of the government. Although civil society organisations are not banned, the ruling majority hampers their activities and international cooperation.

- What can be done to stop these fundamental rights restrictions? What is left is a combination of legal resilience at the supranational level, including strategic litigation at the ECJ and the European Court of Human

- Civil society can consider applying peaceful forms of democratic resistance. Cities under opposition rule may reject and delegitimise government propaganda and directly tackle various human rights problems. Freedom and democracy may also be respected and exercised locally.

In its Summer 2021 report, The NGO Reporters Without Borders calls Hungary a “would-be information police state at the heart of Europe” that censors certain types of speech and forces independent journalists and their sources to censor themselves. The report notes that since coming to power in 2010, Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party has brought the media landscape under its control, muzzled the country’s media and silenced opposition voices.

So, what is left of media pluralism and independent media in Hungary? Can we still expect to encounter a diversity of opinion? This brief analysis will examine the past, present and future of the constitutional structure as it applies to the public sphere, including protection of free speech, media freedom and civil society regulations.

From censorship to freedom of speech

To begin this examination, we should take stock of the situation before the 1989 democratic transition. Hungary’s first codified constitution of 1949 was strongly influenced by the Soviet-style political system. This constitution served as a map of political power and failed to even recognise the existence of human rights. And since the constitution was a sham constitution, it did not provide for the realisation of even the enumerated ‘fundamental rights.’ For instance, the 1949 constitution formally declared free speech and press freedom to be in accordance with the interests of the working class, but even these limited rights were rarely legally enforceable.

1989 is frequently taken as a starting point for qualitative change regarding the constitutional nature of the country. This especially applies to free speech. In one of its earlier decisions, the newly established Constitutional Court placed freedom of expression at the heart of the democratic system and stressed that free speech and media freedom were fundamental to democracy. As the Court elaborated:

“(T)he freedom of expression has a special place among fundamental rights, in effect it is the ‘mother right’ of several freedoms, .… Enumerated rights derived from this ‘mother right’ are the right to free speech and the right to the freedom of the press, with the latter encompassing the freedom of all media, as well as the right to be informed and the right to freely obtain information. … It is this combination of rights that renders possible the individual’s reasoned participation in the social and political life of the community. Historical experience shows that on every occasion when the freedom of expression was restricted, social justice and human creativity suffered and humankind’s innate ability to develop was stymied. The harmful consequences afflicted not only the lives of individuals but also that of society at large, inflicting much suffering while leading to a dead-end for human development. Free expression of ideas and beliefs, free manifestation of even unpopular or unusual ideas is the fundamental requirement for the existence of a truly vibrant society capable of development.” (Decision 30/1992)

Accordingly, the Constitutional Court provided strong protection of free speech: Hungarian free speech constitutional jurisprudence embraced the idea of content neutrality and, at least at that point, the Court was not ready to restrict speech in the interests of social peace. The constitutional basis of media freedom was in line with the European principles of media freedom, and it served to encourage legislators to build a free and pluralistic media system overseen by the National Radio and Television Board. The nomination and election processes for the Board members were based on cooperation and compromise by all parties in parliament.

From freedom of speech to censorship

As we have already described in our first two contributions, Fidesz demolished the institutions established in 1989–1990 and significantly weakened institutions intended to counterbalance executive power, such as the Constitutional Court, the judiciary, and the ombudsperson institution. Similar things happened in the field of free speech and the media. The constitution of the new regime, called the Fundamental Law, contains content-based restrictions: freedom of speech and the press can be denied in the name of the nation, the dominant ethnic group, or religion (Article IX(5). Several anti-LGBT laws has been passed based on these constitutional provisions, including the latest one, which conflates homosexuality with paedophilia, bans LGBT content in schools, TV shows, and films, and requires publishers to put disclaimers on its books with such content. The Fundamental Law has also facilitated the de jure takeover of public media and the de facto capture of the private mass media. Based on these constitutional provisions, the governing majority has undermined the independence of the bodies responsible for overseeing private and public media, controlled access to public information, and manipulated the media and the advertising market. We will examine these steps in turn.

First, the governing majority has introduced a scheme merging the former telecommunications and broadcasting regulatory authorities and established one, powerful National Media and Info-communications Authority. Its head is appointed by the Prime Minister, which – under the given political circumstances – ensures that the government has a considerable influence on the performance of the Authority. The Authority’s head appoints its main decision-makers, nominates the top officials in public service media, and also indirectly employs all journalists in public media. The head of the Authority is also automatically the head of the Media Council, whose task is to regulate and control the Hungarian media. The Media Council consists of members nominated by the governing party, and the consequence of this one-party structure can be seen in the trading of terrestrial frequencies and the way the Council approves acquisitions in the media market.

International bodies have expressed concerns about this institutional design. The OSCE has criticised it, arguing that it “may create conditions for the realisation of the ‘winner takes-most’ or indeed ‘winner-takes-all’ scenario in the current term of parliament, in defiance of the principle of the division of powers and of the checks and balances typical of liberal democracy”. According to the Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights, the provisions regarding appointments to existing media regulatory bodies, as well as their composition and tenure “lack the appearance of independence and impartiality, quite apart from a de facto freedom from political pressure or control”. The European Commission also expressed concerns about the compliance of media legislation with EU law. Following the intervention of the European Commission, the Hungarian parliament softened the rules. However, the remaining provisions allowed the government to ensure that, in the long run, decisions that shape the situation of individual market players and the overall structure of the media system are synchronised with the objectives of the governing parties.

The governing majority has also manipulated the information environment: it has organised the coordinated spreading of messages in the pro-government media and centralised public service broadcasting system, facilitating the spread of biased, pro-government information.

Thirdly, the governing majority has manipulated access to market resources, which has radically changed the media market structure. Arbitrary state interventions have weakened or impeded the financial viability of media outlets that publish critical views about the government. For instance, in 2018, a Hungarian media conglomerate called the Central European Press and Media Foundation (KESMA) was created overnight to take over the ownership rights of close to 500 news outlets. Through this and other similar interventions, an ever-growing array of media outlets in Hungary has ended up in the hands of ‘businessmen’ with close ties to the governing parties; at the same time, some critical media outlets have disappeared (e.g., Népszabadság, Klubrádió). Likewise, an important tool of the governing majority’s media policy has been to distort the advertising market. For instance, the concentrated placement of state advertising has made it possible to ensure that media products that might otherwise be unsustainable in the market remain financially viable.

In short, legislative changes and governmental policies during the last decade have allowed the governing majority to take over public media and control how the main public narratives are communicated via private media. This makes the fact that many citizens rely on public and private media outlets all the more concerning. The audiences of these media outlets and critical (social) media encounter antithetical and mutually contradictory interpretations of reality.

The government’s speech regulation and ‘media policy’ is part of a general project to reshape all sectors and institutions that influence the range of information and opinions in the public sphere, including the third sector, and NGOs in particular.

Since the early 2010s, the government has launched a series of campaigns to discredit NGOs critical of the government’s human rights protection policies. The campaign has taken many forms, from public statements to tax audits and criminal investigations. The Government Control Office has conducted an investigation targeting many NGOs and launched tax audits against several of these organisations. None of these procedures resulted in any findings that the organisations investigated had done anything unlawful.

Recently, the government has started to use legislative action to attack NGOs. The Fidesz party vice‐chairman fired the starting gun when he said, “The fake NGOs that make up the Soros Empire operate in order to compel national governments to serve the interests of big global capital and to succumb to the values of political correctness. These organisations must be forced to back down at any price, and I believe we need to clean them out. My sense is that international developments provide us with an opportunity to do so”. He then added: “They want to intervene in grand politics without any sort of legitimating participation[sic]”.

Accordingly, Parliament adopted a law requiring any NGO that receives foreign funding (including EU funding) over about EUR 26,000 per year, for any purpose whatsoever, to register with a court as a ‘foreign‐funded organisation’. These NGOs had to display a ‘foreign‐funded organisation’ label on their website and publications. In response, the European Commission launched an infringement action, and the European Court of Justice (ECJ) found the NGO law to be inconsistent with EU law. The Orbán government formally complied with the judgment and repealed the law but replaced it with intrusive audits by the State Audit Office. Later, it issued a new decree banning anonymous donations to NGOs.

Another infamous step of the governing majority was to adopt the so-called ‘Stop Soros law’ that changed the Criminal Code by making the provision of support to individuals seeking asylum and residence permits a crime punishable by one year of imprisonment. On 18 July, the European Commission launched an infringement action over the law. Advocate General Santos urged the ECJ to conclude that the criminalisation of civilians who helped migrants was at odds with EU law; the case is still pending before the ECJ. Moreover, a special tax on immigration, or in effect, on free speech was also adopted. A 25 per cent tax is to be levied on any financial support for activities and organisations that ‘support immigration’. International organisations have stated that both provisions constitute illegitimate interference with the freedom of expression.

Furthermore, as a part of the anti-Soros campaign, the Central European University (CEU), widely considered a bulwark of open society and liberal democracy, was targeted by a new law, and compelled by the government to move its centre of operations abroad. The ECJ ruled that the ‘lex CEU’ making the CEU’s operation impossible in the country violated EU law, but the decision came too late for the CEU to return to Hungary.

In short, although civil society organisations are not explicitly prohibited, the governing majority has adopted several discriminatory, inflexible, and costly requirements for registering and operating civil society groups, and for these groups’ reporting activities. Likewise, ‘foreign agent’ laws have been used in Hungary to curb cooperation between international and domestic NGOs. Furthermore, government-organised non-governmental organisations have been financed by the government to imitate civil society, promote autocratic interests, and hamper the work of legitimate NGOs. The Hungarian government is careful to avoid anything that could look like severe violations of fundamental rights. Yet, behind the veil of democracy, systematic abuses of fundamental rights can be found, fundamental rights violations that are deeply problematic according to universal constitutional and international human rights standards.

How to get back to freedom of speech

What can be done to stop these fundamental rights restrictions? The near-complete erosion of democracy, as we described in our previous analysis, drastically limits the possibility of domestic legal resilience against restrictive measures where courts have been politically captured or are otherwise incapable of responding due to a complete lack of judicial independence. What is left is a combination of legal resilience at the supranational level, including strategic litigation at the ECJ and the European Court of Human Rights, and civil resistance at the domestic level.

One might wonder whether the fact that this is all happening in a European Union Member State makes a difference. The conditions for EU membership include the protection of constitutional values: the existence of “stable institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human rights and respect for and protection of minorities”. The primary sanctioning mechanism for values-based non-compliance with EU law is a political process identified in Article 7 of the Treaty on European Union. Article 7(1) allows the European Council to give a formal warning to a country if it finds a risk of a breach of the EU values. If that does not have the desired effect, the Council – subject to certain voting requirements – can impose sanctions and suspend voting rights under Article 7(2) and (3).

At the time of writing, the European Union has continued to adopt a wait-and-see approach (as it has in the past), even as Prime Minister Orbán has assumed increasingly unlimited and unrestrained powers. Although the European Parliament initiated the Article 7(1) process against Hungary in 2018, this procedure is still hanging in the air because the Council has never seen fit to publicly condemn Hungary for failing to meet Europe’s constitutional commitments. The other legal process for ensuring the uniform enforcement of EU law, including the infringement procedure, allows the European Commission to bring a Member State to the ECJ if it violates EU law. But infringement procedures have long been used for relatively technical violations – and nothing so wide in scope as a systemic threat to EU values. In 2018, the European Court of Justice elevated the infringement action so that it can be used to enforce EU constitutional values, giving the Commission a way to protect the constitutional commitments. The new laws introduced to restrict free speech, press freedom and freedom of assembly would have provided ample reasons to challenge Hungary through infringement actions. Of course, the Commission would have had to have been courageous to launch these actions. Yet, at the time of writing, there is little sign of such courage. The fact that the EU handles media companies solely as economic actors and not as contributors to a democratic society does not help either. Perhaps that is why the European Commission proposed a new EU ‘media freedom act’ to give the EU the means to protect press freedom across Europe.

Potential external support for the re-democratisation of Hungary is not limited to the European Union. The European Court of Human Rights is also a venue for resisting further backsliding. The Court has already delivered several important judgments on free speech and the right to asylum, but Hungary has failed to implement earlier rulings. For example, in the Baka v Hungary case, the Court ruled that legal regulations discourage judges and court presidents from participating in the public debate concerning the independence of the judiciary. The Committee of Ministers, examining the execution of the Baka judgment, noted “with grave concern” that the chilling effect on the freedom of expression in general “has not only been addressed but rather aggravated”. Another difficulty is that the Strasbourg Court requires complainants to exhaust domestic remedies, including remedies before the Constitutional Court. Yet, the Hungarian Constitutional Court is no longer functioning as a proper independent constitutional court. Furthermore, the absence of any time limit before the Constitutional Court for deciding complaints make this a slow and uncertain route to justice.

The dismantling of democracy and the rule of law leaves little room for legal resilience, but civil society can consider applying peaceful forms of democratic resistance. There are historical precedents for such resistance: for instance, the strategies of resistance developed during feudalism (e.g., the tradition of ‘free cities’) and socialism (e.g., ‘samizdat’ dissident activity). According to medieval traditions, free cities may function as islands of freedom and even exercise self-governance. Cities under opposition rule may reject and delegitimise government propaganda and directly tackle various human rights problems. Freedom and democracy may also be respected and exercised locally. It is significant, then, that on 16 December 2019, the so-called Free Cities Pact was signed by the mayors of Bratislava, Budapest, Prague, and Warsaw to demonstrate their commitment to democratic values and increase their leverage against the national government. Another form of resistance, widespread during socialism, is the maintenance of an ‘alternative’ sphere of public information. Social media naturally provides it, but collective or ‘social’ intelligence can also be used to generate verified information and reliable data. In Hungary, ‘samizdat’ literature is once again being circulated. Radio Free Europe is back on the scene, and in March 2021, the German state broadcaster Deutsche Welle relaunched Hungarian-language news programmes for the first time since 1999. These developments may help ensure the free flow of information necessary to make the government more controllable and accountable.

Kriszta Kovács and Gábor Attila Tóth

* Photo: Viktor Orbán, author: European People’s Party. Source: Flickr (CC BY 2.0).