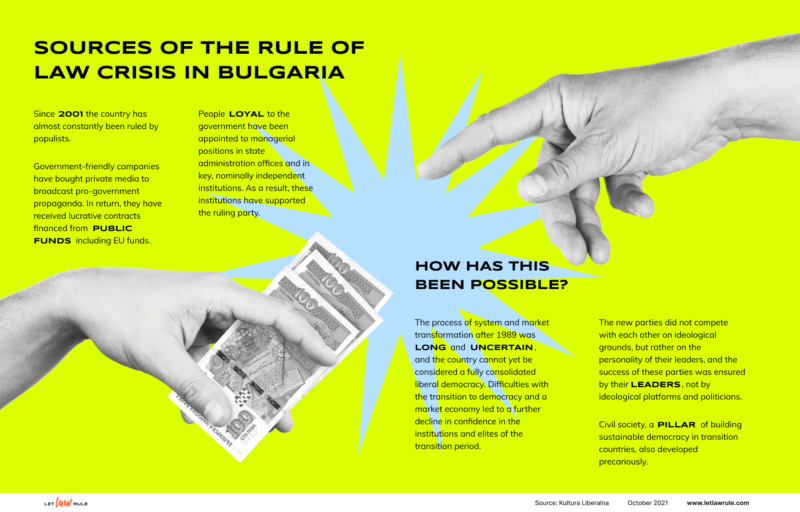

To better understand the current state of Bulgarian democracy and rule of law, it is important to elucidate the sources and reasons behind their weakness. At the most general level, one major factor is that since 2001 the country has almost entirely been ruled by populists of different hues and ideological stripes.

- There are many factors that may help explain how this dire state of liberal democracy in Bulgaria came about. First, the country’s long and hesitant transition to market democracy and the rule of law should be pointed out. The country has arguably yet to achieve full consolidation of its liberal democracy.

- Bulgaria has a problems with the rule of law, the independence of the judiciary, the fight against corruption and organized crime, freedom of expression and media independence.

- To better understand the current state of Bulgarian democracy and rule of law, it is important to elucidate the sources and reasons behind their weakness. At the most general level, one major factor is that since 2001 the country has almost entirely been ruled by populists of different hues and ideological stripes.

- To ensure comfortable media coverage of populists in power, government-friendly businesses buy private media outlets, often financially supported through lucrative publicly-funded contracts, including with EU funds. Public media has also been taken over by packing the media regulators with party loyalists and changing the management of the public media companies, which subsequently become mouthpieces for the populists in power.

Since the country joined the European Union (EU), there has been almost no mention of Bulgaria in the international press that has not begun by stating that it concerns the poorest and most corrupt EU member state [1], be it yet another mass anti-government protest, a new European Commission (EC) report, or another international organization monitoring the country’s democratic process. In academic and policy publications Hungary and Poland are usually cited as the clearest examples of the collapse of democratic institutions in Central and Eastern Europe. However, while until relatively recently being the leaders in democratization of the region, the erosion of democracy and the rule of law are both now in full effect. If Bulgaria rarely grabs the international headlines in that regard, it is mostly due to the lowered expectations towards it due to the lagging and incomplete consolidation of liberal democracy there [2], and not because it has no problems or because these problems are less pronounced than they are with the usual suspects – the “bad boys” of the region, Poland and Hungary.

The purpose of this series of articles is to briefly outline the trajectory that led to the dire state of democracy and the rule of law in Bulgaria. The focus is on a series of populist governments that have not only failed to achieve lasting solutions to the country’s corruption and rule of law problems, but also deepened them. This led to a situation in which the country’s partners were forced to abandon diplomatic language and openly talk about “endemic” corruption and a “captured state”. The US government even imposed unprecedented, far-reaching sanctions under the global Magnitsky Act [3] against a Bulgarian businessman, a politician and Government employees. After 15 years of unprecedented monitoring of the country in the fields of the rule of law and the fight against corruption under the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism (CVM) [4]- the periodic monitoring imposed by the EC on Bulgaria and Romania after these countries’ accession to the EU in 2007, this mechanism has not yet been fully lifted. Moreover, in the first reports (autumn 2020 [5] and summer 2021) [6] within the new common mechanism for annual monitoring of the rule of law in the EU [7]recently introduced by the EC, Bulgaria is again in the league of the most problematic, most often mentioned as experiencing serious ‘challenges’ MS [8].

Populist rule

To better understand the current state of Bulgarian democracy and rule of law, it is important to elucidate the sources and reasons behind their weakness.

At the most general level, a major factor is that since 2001 the country has almost entirely been ruled by populists of different hues and ideological stripes (the only exceptions to this have been a short break between 2005 and 2009 under Stanishev’s ‘triplec coalition’ government, and for a year from June 2013 under the Oresharsky government).These range from the soft pro-European technocratic populism of the Simeon Saxe-Coburg-Gotha’s (ex-king of Bulgaria) government (2001-2005), through the moderate pro-EU technocrats of GERB’s first (2009-2013) and second (2014-2017) governments, to the radical right, nativist populism of United Patriots – the minor coalition partner in the third GERB government (2017-2021).

The key feature of populism in power [9] is that by concentrating power in the hands of charismatic leaders catering for the interests of their expanding clientelle, it promotes ‘democratic illiberalism’ [10] by undermining key institutions and values of the liberal democratic state. This most notably affects its liberal components – rule of law instruments such as independent courts and other rights-protection institutions, and the system of checks and balances. In their attempts to stay in power, they often also corrupt the electoral process by tweaking electoral laws in their favour, by illegitimately using state resources – including disproportionate coverage in the public media – in their campaigns [11] and by using, and according to their political opponents, even capturing the electoral administration at the local [12] if not at the national level.

To ensure comfortable media coverage of populists in power [13], government-friendly businesses buy private media outlets, often financially supported through lucrative publicly-funded contracts, including with EU funds [14]. Public media – whereever it exists and has influence in society – is also taken over by packing the media regulators with party loyalists and changing the management of the public media companies, which thereby often turn into a mouthpiece for the populists in power. All this drastically worsens the media environment – it is not an accident that in recent years the country has systematically received the lowest ratings among EU countries [15] in a number of prestigious rankings for media freedom. This prevents the media from fulfilling its main function in democratic regimes – to serve as a channel for exercising democratic control and ensuring democratic accountability of the government.

Filling leading positions in key, nominally independent, regulators and executive agencies, as well as generally packing the state administration both at the national and at the regional and local levels with party loyalists who then work to turn the state into machine in support of the party-in-power, are further features explaining both why populists have been able to stay in power so long and why the damage they continue to inflict on the institutions and practices of the liberal-democratic state are so lasting and deep.

Erosion of trust

There are many factors that may help explain how this dire state of liberal democracy in Bulgaria came about.

First, the country’s long and hesitant transition to market democracy and the rule of law should be pointed out. The country arguably did not achieve full consolidation of its liberal democracy [16].

Secondly, the difficulties of the triple transition [17] to democracy and market economy have led to a further decline in levels of trust (already low at the beginning of the transition) in institutions and, in general, in the elites of the transition. As of 1998, for example, 44% of Bulgarians do not trust political institutions [18], which is almost twice as high as the CEE average (28.1%), and significantly exceeds the average values of distrust in institutions typical of developed democracies. In 2008, more than 90% of Bulgarians stated that they had no or little trust in political institutions [19].

This erosion of trust in the institutions and elites of the transition contributed to the emergence of one of the first successful populist political projects in CE [20] after the announced (seemingly too hastily) final triumph of liberal democracy [21] – the political movement of the former Bulgarian tsar Simeon II. With his coming to power, Bulgaria’s bipolar party model [22] – in which the main cleavage was along the axis of communism/anti-communism or “left/right” – came to an abrupt end. This marked the beginning of the domination of the country’s political system by series of populist players. The source of their success was fatigue from the transition and the politicians who led it, as well as the desire to catch up faster with “normal European countries” – the leading, largely de-ideologized, political ideal for a majority of Bulgarians.

After the moderate populism of Simeon II’s government, which quickly took its place in the country’s political system as a mainstream political player, the Bulgarian political system experienced a second shock with the entry of ultra-nationalist and far right, nativist forms of populism – such as the Ataka party. A peculiar kind of hybrid between media and party [23], this political project sprang up in 2005 from yet another substitute for the missing ideology in the Bulgarian political space [24] – the popular nationalist show Ataka on a local cable television. In 2009 it became an important crutch of the third significant populist party in the country – GERB. The latter’s charismatic leader, Boyko Borissov, ruled the country for the next 12 years (with a short break), with GERB being the largest political force in all parliamentary elections from 2009 to 2021. Amids a political crisis with an unclear end, in the early elections in July 2021 а fourth populist project – another party-media hybrid, called “There is such a people’ (ITN), led by the showman Slavi Trifonov, garnered the most votes,.

New political projects

Third, the exhaustion of the mobilization potential of the ideological clashes from the first decade of the transition along the communism / anti-communism axis has been at the heart of the search for new mobilization strategies. Thus, new political projects increasingly rely on the personality of their leaders for their success, rather than on ideological platforms and policies. As the demand for parties with a strong ideological profile has declined after a decade of sharp ideological confrontation – which not only failed to achieve the national goal of catching up with Western democracies, but also did not improve overall quality of life – political supply also turned to political products with a more or less populist character. Thus, a series of charismatic leaders are vying to promise a quick escape from the hardships of the transition and sharp improvement of the situation in the country. The dominant political model in the country became that of the personalist party [25].

Another compensatory form for the lack of mobilization potential of the de-ideologized political players is the above-mentioned media-party hybrid. In addition to the Ataka party led by the journalist Volen Siderov and ‘There is such a people’ led by the TV presenter Slavi Trifonov, there is at least one more significant case when a TV presenter has become a party leader – that of the journalist Nikolay Barekov and his party, ‘Bulgaria without Censorship’ (BGWC). What unites all these projects – apart from the mobilization around the media and the charismatic leadership of a TV personality – is the strong anti-corruption message and the typical populist demonization of the existing elites as “corrupt” traitors of the people’s interests.

Slowly developing of civil cociety

Fourth, civil society – a pillar for building sustainable democracy in transition countries and a necessary check on deconsolidation processes – was developing slowly and hesitantly [26] both in Bulgaria and in other “new” democracies. It is no accident that analysts identify the “hollow” democratic institutions [27] as one of the main reasons for the weakness of post-communist democracies. It has convincingly been argued that democracies in some CEE countries, including Bulgaria, were born with a “hollow core”[28]; from the very beginning lacking (and failing to subsequently develop) the most important elements for building vital democracy – mass civic participation and sustainable civil society. Indeed, analysts further show [29] that in Bulgaria the vast majority of NGOs were established in the early 1990s with external assistance and external funding, and later weakened or even ceased to function after the withdrawal of external support following the country’s accession to the EU. Only a small percentage of them have managed to attract enough long-term support in society to be sustainable over time and to be able to achieve their goals of effective control over institutions and the involvement of citizens in democratic processes.

The involvement of citizens in various formal and informal organizations, volunteering, and other forms of civic participation is low [30] in Bulgaria, as is the case in other post-communist societies since the beginning of transition, which is often explained by the effect of communist rule, which atomized societies and demobilized citizens, confining them in their close family circles.

Bulgarians’ horizontal trust of their fellow citizens – which should compensate for the low “vertical” trust in the institutions, not only did not improve, but in fact decreased in Bulgaria during the transition. [31] At the beginning of the transition, in 1990, public trust in institutions was at 33% (higher than that of a number of other post-communist societies at the same time), but by 2008, immediately after the country’s accession to the EU, it had eroded to just 17.7% .[32].

Weakened civil society in Bulgaria has failed to mobilize for effective resistance against a series of governments that, in the name of “fighting corruption” and resolutely improving the situation, instead concentrate power around their charismatic leaders. The result of this concentration is a deterioration in the quality of the democratic process and an erosion of democratic institutions, a reality which is reflected in the assessments by organizations monitoring the state of democracy in the country. For example, although the country is still assessed as “free”, reports on Bulgaria in the Freedom house’s Freedom in the World study [33] have for years cited growing problems in the field of rule of law, independence of the judiciary, the fight against corruption and organized crime, freedom of expression and media independence, and accordingly, the country continues to receive lower scores in these fields.

Finally, due to the weaknesses of the Bulgarian civil society outlined above (primarily low horizontal trust and social capital) high levels of public protest have unfortunately failed to achieve lasting improvement, and instead often support the rise and success of yet another populist project.

Indeed, periodic mass outbursts of civil anger provoked by shocking cases of seizure of power by illegitimate or compromised political and economic players – such as the 2013 [34] and 2020 [35] anti-government protests – have been largely unsuccessful. This is mostly due to the fact that protests are organised by several political entities, which so far have failed to effectively coordinate to achieve lasting political success. Instead, the energy is channeled and often fuels populist projects, often funded by the same individuals who provoked popular anger. The most striking such case was the protest in early part of 2013, which led to the rise of Nikolay Barekov’s political project “Bulgaria without Censorship”. It was financed by the banker Tsvetan Vassilev, owner of the so-called “bank of the government”, the corporate commercial bank KTB (for detailed information about KTB and the political and economic processes and players behind the ‘bank bankruptcy of the century’, see the website of the “KTB – what happened” project [36]. Tsvetan Vassilev – and what his bank symbolized, namely the oligarchic merger of economic and political interests – was one of the figures (along with the media mogul and DPS politician Delyan Peevski) against whom tens of thousands protested in 2013. Again, in 2021, the mobilization of the mass anti-government protests from 2020 fed not only the political entities directly involved in the protests, but also political players such as Slavi Trifonov and his ‘There is such a people’ (ITN) movement. The latter won the early elections in July 2021 without being directly involved in the protests. Moreover, ITN’s controversial political behavior after the elections – effectively subverting the possibility to form a pro-reform government with rule of law reform high on its list of priorities – has raised doubts [37] among both politicians [38] and analysts [39] about its ultimate motivation. What is clear is that its moves betray the mass impetus for change that led to its recent electoral victory and may ultimately undermine the causes that motivated voters to support it.

Summary

A short summary cannot do justice to the multiple sources of the erosion of liberal democratic institutions and the reasons behind the rule of law crisis in Bulgaria. Nevertheless, this paper has outlined the main weaknesses of the political model in post-transition Bulgaria and also the shortcomings stemming from the transition – and even from the communist legacy – which have provided the background for these worrying developments. The next piece will look in some more detail into the actors and will sketch the mechanisms through which the erosion of liberal-democratic institutions in Bulgaria during the post-ЕU-accession period came about.

Ruzha Smilova PhD

Centre for Liberal Strategies

Footnotes:

[1]https://www.euronews.com/2020/09/02/bulgaria-unrest-voices-from-protests-demand-to-be-heard-in-brussels

[2]https://muse.jhu.edu/article/607613

[3] https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0208.

[4]https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/upholding-rule-law/rule-law/assistance-bulgaria-and-romania-under-cvm/cooperation-and-verification-mechanism-bulgaria-and-romania_en

[5]https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/2020-rule-law-report-communication-and-country-chapters_en

[6]https://ec.europa.eu/info/files/communication-2021-rule-law-report-rule-law-situation-european-union

[7]https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/upholding-rule-law/rule-law/rule-law-mechanism_en

[8]https://www.rferl.org/a/hungary-bulgaria-romania-criticized-in-eu-rule-of-law-report/30866473.html

[9] https://www.journalofdemocracy.com/articles/populists-in-power/

[10]https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/oso/9780198837886.001.0001/oso-9780198837886

[11]https://www.novinite.com/articles/208805/International+Observers+of+Bulgaria%E2%80%99s+Elections+2021+Gave+Press+Conference

[12]https://eurocom.bg/new/republikantsi-za-blgariya-borisov-i-dps-izpolzvat-izbornata-administratsiya-v-svoya-polza

[13] https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057%2F9781137337849_13

[14] https://www.rcmediafreedom.eu/Publications/Reports/Bulgaria-media-ownership-in-a-captured-state

[15]https://seenews.com/news/bulgarian-media-least-free-in-eu-see-amid-smear-campaigns-state-harassment-rsf-738504

[16] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jcms.12845

[17] https://www.jstor.org/stable/40970678

[18]https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318641571_The_Duty_to_Obey_the_Law_and_Social_Trust_The_Experience_of_Post-Communist_Bulgaria

[19]https://osis.bg/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/OSI_Publication_Public_debate_4.pdf

[20]https://www.isp.org.pl/uploads/drive/oldfiles/7832124490738466001218629576.pdf

[21] https://www.jstor.org/stable/24027184

[22]https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/sofia/07777.pdf

[23]https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198747536.001.0001/acprof-9780198747536-chapter-13

[24]https://www.springerprofessional.de/en/democracy-and-the-media-in-bulgaria-who-represents-the-people/7290712

[25] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2753/PPC1075-8216600101

[26]https://muse.jhu.edu/article/17178/summary

[27] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1758-5899.12225

[28] https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.7591/9780801465666/html

[29]https://www.erstestiftung.org/en/publications/civil-society-in-central-and-eastern-europe-challenges-and-opportunities/

[30]https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/weakness-of-civil-society-in-postcommunist-europe/AF9F78570C27B1A5666746C205BA1AA0

[31]https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318641571_The_Duty_to_Obey_the_Law_and_Social_Trust_The_Experience_of_Post-Communist_Bulgaria

[32]European values Survey 1990, 2008.

[33]https://freedomhouse.org/country/bulgaria

[34]http://worldpolicy.org/2013/12/17/2013-the-year-of-bulgarian-protest/

[35]https://www.euronews.com/2020/10/17/bulgaria-protests-enter-100th-consecutive-day-as-demonstrators-denounce-widespread-corrupt

[36] http://www.ktbfiles.com/about-the-project/

[37]https://www.politico.eu/article/slavi-trifonov-election-bulgaria-government-coalition-majority-corruption/

[38] https://debati.bg/tatyana-doncheva-itn-i-dps-deystvat-zaedno/

[39]https://www.mediapool.bg/analizatori-za-kabineta-78-realen-e-riskat-za-podmyana-a-ne-promyana-news324095.html